DISORIENTALISM

Asian Subversions, Irish Visions

by

Ciaran Murray

The Asiatic Society of Japan

Introduction

‘Why is Dublin Castle like a temple garden? Why is Whistler’s Irish lover like a woodblock print? Why is Hemingway’s Irish warrior like a Noh play?

‘The answers involve the arts of Europe over two and a half centuries; and, given the superabundance of the material, one can only adopt the method suggested by Strachey: “The…explorer of the past…will row out over that great ocean of material, and lower down into it, here and there, a little bucket, which will bring up to the light of day some characteristic specimen, from those far depths, to be examined with a careful curiosity”.

‘Irish literature provides just such a sample. More to the point, it provides a sample from the core. The Romantic sublime is defined by Burke; Wilde is the supreme exemplar of Aestheticism; and at the centre of Modernism stands Yeats’.

PART I: Aesthetics

1. Kyoto’s Temples to Tara’s Halls. Romanticism, with its valuation of the Japanese garden over the French, the natural over the artificial, the indigenous over the alien, is adapted for Ireland when Henry Brooke champions Celt against Roman and his daughter Charlotte publishes a bilingual collection of Gaelic poetry. ‘It should not be necessary at this stage to rehearse the tale of Macpherson’s Ossian. However, it is possible, while telling the truth and nothing but the truth, by failing to tell the whole truth create all the effect of falsehood. The salient fact is that the language of Scotland derived from Ireland, together with a literature of very archaic antecedents, including such personages as Fionn or Finn, originally the Celtic sun-god, whose son Oisín or Ossian went to live with a golden-haired woman under the western ocean. After the reduction of such divinities to time and mortality, he was ingeniously brought back to be baptised by St. Patrick. However, the poets had their revenge when they imagined dialogues between the two in which Oisín, as against the asceticism of the new religion, upheld the joyousness of the old, and especially its love of nature. These poems, long acclimatised in Scotland, provided the materials for Macpherson: who disguised or eliminated Patrick as an unwelcome witness to their origin; and went on, to the dismay even of his well-wishers, to invert history by making Scotland the source of Gaelic literature and Ireland its shadow.’

2. Lady Morgan & the Moonlight Menace. Owenson inverts the implications of Burke’s aesthetics by locating his beautiful in England and his sublime in Ireland. ‘The polarity between the natural and the artificial had been dramatised by Rousseau in La Nouvelle Héloïse, and by Goethe in Die Leiden des jungen Werthers. Owenson, accordingly, gives the hero of St. Clair an upbringing in Rousseau’s native Switzerland, to which she assimilates the wilder landscapes of Ireland; and, as Goethe had invoked the poems of Ossian, follows Charlotte Brooke in reclaiming these for her own country… If all her places were Ireland, all her protagonists were herself, lightly disguised or in fancy dress. Life imitated art. She was loudly applauded when she appeared at the theatre in a “red Celtic cloak…fastened by a rich gold…Tara brooch”. When, like her Wild Irish Girl, she married an Englishman, in the process becoming Lady Morgan, even he addressed her as Glorvina, the heroine of this most celebrated of her creations. And, when she dashed through the streets of Dublin in a high, springy, unstable carriage that in form and tint resembled a grasshopper, driven by her scholarly husband in matching spectacles, she anticipated, in symbolic colour and incorrigible panache, her young contemporary of the green carnation’.

3. Oscar Cancels a Country. Wilde repudiates Romanticism in favour of Aestheticism: the movement of thought, from Kant to Gautier, that came to him through Whistler’s valuation of the Japanese woodblock print. ‘”The whole of Japan”, declared Oscar Wilde in The Decay of Lying, “is a pure invention. There is no such country, there is no such people”. We know, of course, what he meant; but there is a sense in which it might be said that for Wilde there were two such countries as Japan. He was born into one, and adopted into the other. The one stood for nature, the other for art… That life could imitate art was evident from Wilde’s surroundings. He lived in a house in Chelsea which a visitor identified in a fog by means of its white door. The door was opened to a young Irish poet, who found inside “a white drawing-room…and a dining-room all white’ – ‘chairs, walls, mantelpiece, carpet”. To all this glare of whiteness there was a single exception. The poet remembered ‘a diamond-shaped piece of red cloth in the middle of the table under a terracotta statuette, and, I think, a red-shaded lamp hanging from the ceiling to a little above the statuette’. Such were the recollections of Yeats; who noted also that the scheme ‘owed something to Whistler’… Wilde had in fact settled in the same street as Whistler, the street where stood that home of his which was known as the White House. It had been designed by the architect Wilde later employed, a friend who shared Whistler’s fascination with Japanese art. The result was a façade in which doors and windows were set where needed, in a natural asymmetry. The exterior of Whistler’s house, then, evoked that first Japan of the imagination, the irregularity of whose gardens had migrated to the picturesque building. Whistler’s interiors, too, anticipated Wilde’s, including a room in white and terracotta; but this was merely part of an overall pattern that involved the second Japan of the imagination. So convinced was Whistler of the superiority of art to nature that he declared the night sky overcrowded…

So it was that the two Japans converged. The street where Whistler lived looks out today across the Thames, between the trees that line either bank, to a golden Buddha on the further shore. Here it was that Wilde read to Yeats from the proofs of The Decay of Lying. There was no such country as Japan.’

PART II: Archetypes

4. Japan as Celtic Otherworld. See below.

5. Byzantium and the Mandala. Yeats, following William Morris, locates Jung’s archetype of the centre, representing integration of the psyche, in the city which unites east and west, north and south. ‘Yeats’ vision of Byzantium, Thomas McAlindon has recognised, owes much to Morris and for Morris it was a living centre of the arts, of the fusion and diffusion of influence… From “Bokhara to Galway”, he writes, “from Iceland to Madras, all the world glittered with its brightness”. It is difficult indeed to overestimate its centrality. The only city to span Europe and Asia, it was located where two trade-routes crossed, “the sea-channel between north and south and the land-bridge between east and west”… It had stood on its crossroads for a thousand years when the first Christian emperor made it his capital… To its Russian converts, Byzantium was Tsarigrad, city of the emperors; and, though it fell to the Turks in the fifteenth century, their own tsars flew to the twentieth the double-headed eagle of the house of Palaeologus. For Morris, however, the glory of Byzantium belonged pre- eminently to the decorative arts…So that when Yeats describes Byzantium as a place where “religious, aesthetic and practical life were one”, he adds the dimension of religion to Morris’ conjunction of the aesthetic and the practical. Yeats’ Byzantium, then, is a vertical as well as a horizontal meeting-place; and this too is characteristic of the mandala. “The centre”, declares Eliade, “is pre-eminently the zone of the sacred”. Rome, designed it is thought as a square within a circle, was seen as the axis of heaven, earth and hell. Babylon, likewise, was Bab-ilani, “gate of the gods”, for it was there that they descended to earth. The same held true for Jerusalem: it was set on the site of the Earthly Paradise – that lifetime ideal, in one form or another, of Morris. It was the burial-place of Adam; whose name, in an ingenious play on the Greek initials of the four quarters – anatolē, dysis, arktos and mesēmbria, or east, west, north and south – further reinforced the symbolism of the sacred centre: that heart of the mandala where enlightenment is attained. “The various quarters of the city”, recalls Jung of a dream, ‘were arranged radially around the square. In the centre was a round pool, and in the middle of it a small island. While everything…about was obscured by rain, fog, smoke, and dimly lit darkness, the little island blazed with sunlight. On it stood a single tree, a magnolia, in a shower of reddish blossoms. It was as though the tree stood in the sunlight and was at the same time the source of light’. Likewise, at that centre of the spiritual life which he called Byzantium, Yeats found a tree of gold’.

6. Shimmering. The archetype is further developed by Yeats in the alchemical imagery common to Europe and Asia, and identified by Jung with the process of enlightenment. ‘Plato devalues those forms of intelligence which do not involve measure; one recalls the injunction over his door: ‘let no-one ignorant of geometry enter’. Geometry seemed to substantiate the reality of eternal forms: of an order the discernment of which was the highest reach of wisdom. Yet the goddess of wisdom was Athena, and her accomplishment was of a very different kind. It was known as mētis, which is better rendered as “craft”: craft as cunning and craft as creation. The two were seen as the same in some invention which displayed ingenuity, the ship’s oar or the horse’s bit. “Every Colonus lad or lass discourses”, exclaims Yeats, translating Sophocles, “Of that oar and of that bit”: for which Sophocles gives the credit to Poseidon. Certainly the sea was his domain, as was the equally unpredictable energy of the horse, an analogy underscored when Yeats speaks “Of horses and horses of the sea, white horses”. So much for sovereignty; but as far as skill was concerned, this was the realm of Athena. The oar referred to is the steering-oar: so that what we have in either case is a means of guiding, of coming to terms with, an ultimately untamable natural force. In Corinth, Athena was worshipped as a horse-goddess, Athēnē Hippia, who was also known as Athena of the Bit, Athēnē Chalīnitis. And at Athens, on the night before the sea-battle of Salamis, a horse’s bit was placed on her altar. Athena also was the patron of ship-building: another connection in which we use the term “craft”. It is craft – instinct enriched by experience, and not the measuring-line – which enables the shipwright to cut a keel over the grain of the timber, or the pilot to trace a path over the swirls of the sea. Indeed, the same verb – ithunein, “to drive straight” – is used in both cases, as also of the skill of the charioteer. Here, one might observe, is intelligence at work in the field of action rather than abstraction. Another verb of similar connotation is stochazesthai, “to aim straight”, a technical term from archery: which may serve to remind us that mētis is connected with an older layer of the psyche, a layer which goes back to a time when we were a hunting species. At the battle of Salamis, again, the same strategy, or stratagem, was used as in fishing: the Greeks surrounded the numerically superior target shoal, or fleet, confusing them, driving them in on one another; and then moved in for the kill. In like fashion, a fishing-net was used to annihilate Agamemnon. And it is Agamemnon’s comrade-in-arms, Odysseus, who is the supreme exemplar of mētis. It is his craft, embodied in the wooden horse, which brings down the city of Troy. The Iliad, though it does not explicitly describe this dénouement, implies it in its last line, and indeed in its last word: Hōs hoi g’amphiepon taphon Hectoros hippodamoio. “So stood they then at the tomb of Hector, tamer of horses”. The Trojans have lost their horse-tamer, and now are liable to destruction by the uncanny power of the animal’.

PART III: Apophasis

7. Buddha in the Buried City. In ‘The Statues’, Yeats distances himself from the Hīnayāna Buddhism of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Spengler; but elsewhere distinguishes this from the Mahāyāna Buddhism that has been assimilated to Hinduism. ‘Yeats’…life was bracketed by Hindu influence, from Mohini Chatterjee to Shree Purohit Swāmi, both of whom translated the Bhagavad-Gītā, or “Song of the Lord”: that much-loved lyric which has been called “the keystone of Indian spirituality”. Shah observes that it went on echoing in Yeats’ mind; and he notes, too, that all his life he remained a warrior. We may recall that the Gītā is an extract from, or interpolation into, the epic Mahābhārata: it is a close-up on the battlefield where the Indian Achilles, Arjuna, sees relatives of his own on the opposite side, and feels disheartened at the slaughter that must ensue. In this impasse, he is encouraged by his charioteer, who is none other than Lord Krishna; and who tells him what Lucan relates of Celtic belief, and Yeats repeats in “Under Ben Bulben”: that in reality there is neither killing nor being killed. And, he further informs him, as a member of the warrior class it is his karmic duty, the duty of his present incarnation, to take on this battle. The secret of such duty, Krishna continues, is equanimity, “holding equal pleasure and pain, gain and loss, victory and defeat”; and this, I feel, explains a detail in “Under Ben Bulben” that is otherwise extremely puzzling. Here are the ghostly warriors who appeared so long ago in the lines of Yeats; but now they are credited with “completeness of their passions won”. Reality, then, is to be found, not in the delirium of war, but in waging it with dispassion; not in the east nor in the west, but in the still centre. The peace of the battlefield is to be found, says Arjuna’s charioteer, in being “free from dualism, rooted in the real, detached, possessed of one’s soul”: nirdvandvo nityasattvastho, niryogakshema ātmavān’.

8. Some Versions of Nothing. See below.

9. Métaphysique Nocturne. See below.

Summary

This is a study in creative disorientation, specifically that of Europe by Asia. It is a connected series of case studies of Irish writers through the three movements of Romanticism, Aestheticism and Modernism: influenced, respectively, by the Japanese garden, woodblock print and theatre; together with their literary, artistic, psychological, philosophical and spiritual implications. Along the way, it frames figures from other lands in unexpected and revealing vistas. It will appeal to those concerned with any or all of these subjects, with comparative culture, the movement of ideas, the ways of the mind (conscious and unconscious); or, quite simply, imagination.

‘Intellectually rigorous and intellectually exciting’ – Robert Morton, editor, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan.

‘Outstanding scholarship, sensibility and enthusiasm’ – Ken’ichi Matsumura, translator, The Voyage of Bran to the Land of the Living.

‘How beautifully sculpted are the sentences that float on the sea of references and background’ – David Burleigh, editor, Helen Waddell’s Writings from Japan.

‘A stimulating work which bravely “goes it alone” as far as trends and cliques go. A rich feast indeed’ – Nicholas Meihuizen, author, Yeats and the Drama of Sacred Space.

‘Very clearly a labour of love, as well as a meticulous and invigorating work of scholarship...surprising turns and swift insights on every page...opening up new vistas of thought and inheritance’ – Robert Welch, editor, The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature.

‘A marvellous work’ – Charles De Wolf, translator, Akutagawa Mandarins.

‘Unique command of western and eastern culture...stunning’ – Christopher Murray, author, Yeats & the Noh.

‘Magical book’ – Cleo McNelly Kearns, author, T. S. Eliot and Indic Traditions.

‘Fascinating and illuminating’ – Fintan O’Toole, Irish Times.

‘Provided…delightful discoveries for this reader… Murray dips…into the works of Yeats again and again…and each time, we see another facet of the poet; …does not attempt to explain Yeats, but insights accrue in the process of reading’ – Beverley Curran, Journal of Irish Studies.

‘An extraordinary mix of research and imagination… Murray has accounted for a lifelong recognition of the other in his studies and in his travels. He has found Japan in Ireland and Ireland in Japan and left the rest of us directions’ – Charles Canning, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan.

‘We have prized the disquisitions by Ciaran Murray on Japanese and Irish culture and the multiple, sometimes mystical, links between them’ – Carol Gluck, George Sansom Professor of History, Columbia University.

‘Full of gems’ – Dorothy Britton, author, Rhythms, Rites and Rituals: My Life in Japan in Two-step and Waltz-time.

Japan as Celtic Otherworld

‘NEVER believe anything’, warned Rudyard Kipling, ‘that Mister Oscar Wilde tells you’. The occasion was his arrival in Japan:

This morning, after the sorrows of the rolling night, my cabin port-hole showed me two great grey rocks studded and streaked with green and crowned by two stunted blue-black pines. Below the rocks a boat, that might have been carved sandalwood for colour and delicacy, was shaking out an ivory-white frilled sail to the wind of the morning. An indigo-blue boy with an old ivory face and a musical voice was hauling on a rope. Rock and tree and boat made a panel from a Japanese screen, and I saw that the land was not a lie.

Another visitor was so bemused by the correspondence between aesthetic and actuality that he spoke of landscapes in which one was tempted to look for the painter’s seal in some corner.

i

This was the Japan that Lafcadio Hearn was to make his own. Yet it was to be expected that his vision should have been influenced, not by the Japanese aesthetic alone, but the European sensibility it had helped to shape. An early preoccupation with Gautier led to his translating such tales of exquisite sensation as that of the youth, lover of the perilous and the unachievable, who for the sake of a night with Cleopatra goes ecstatically to his death: who ‘wore the ardent and luminous look of one in ecstasy or vision’; for whom, having ‘reached the goal of his life’, there was ‘nothing in the world left for him to desire’; while for the sated queen the exquisite sensation is to see him do so. The ‘exorbitant fantasies’ of both are set in conscious opposition to the calculation of the bourgeois, ‘the nothingness of uniformity’; and are characterised as a ‘wild ardour of senses as yet untamed by the long fast of Christianity’.

This opposition is further explored in the tale of the priest haunted for a lifetime by a face glimpsed at his ordination: who is dutiful curate by day and courtesan’s dandy by night; and, both roles seeming equally real, is torn apart by the two. The dilemma is only resolved when he discovers that his lover is a visitant from the land of the dead; and this story is echoed in one Hearn would retell from the Japanese. There is a sense, then, in which it might be said that he had lived in Japan before ever he landed there.

ii

There is another sense, too, in which it might be said that he brought his Japan with him. There is a scene in one of those poems which he titled Voyages in which Hart Crane realises that his lover’s dreams are a terra incognita to him, a land peopled by strangers; and across the silence which bounds it, he cries:

Your breath sealed by the ghosts I do not know: Draw in your head and sleep the long way home.5

It is those shadows, one may reflect, inhabiting the inner world of the other, which have formed that other, so making possible the current encounter. In like fashion, one might suggest, the voyager may be possessed by phantoms – ancestral images, archetypal patterns – which will shape the engagement with other worlds.

Hearn’s life has been likened to an odyssey, an acquaintance writing of him: ‘I have somewhere read of a nomad child of the desert, born and rocked upon a camel, who was ever thereafter incapable of resting more than a day in one place’; and Hearn himself speaks of the ‘civilised nomad, whose wanderings are… compelled by certain necessities of his being…whose secret inner nature is totally at variance with the stable conditions of a society to which he belongs only by accident’. This he tends to trace to some ‘ancestral habit’, or the ‘development of desires long dormant in a chain of more limited lives’. When he glosses Tennyson’s Ulysses on

that untravell’d world, whose margin fades

For ever and for ever when I move,

he does so in epistemological terms: ‘As from a window of a gate we look out toward the horizon, so from our knowledge we obtain a glimpse of the line which divides the knowable from the unknowable’; and his odyssey was spiritual as well as literal. His birth amid the isles of Greece was followed by an upbringing amid the insularities of a puritanical Ireland: so that one can readily understand the appeal to him of the ‘voluptuous delicacy’ of Gautier. Another of the tales of his that Hearn translated relates the visit of a student to Pompeii, where a woman, the outline of whose body he has seen preserved in the volcanic ash, appears to him in vision, but is banished by a disapproving Christianity. This opposition between classical beauty and Christian asceticism is counterpointed by a contrast between the glowing sunshine of the south and the dense fogs of the north.

All this had personal resonance for Hearn, who thought he remembered Greece as a land of more intense light, in contrast to an Ireland of sinister shadow: when he is taken into a Dublin church, it induces a sensation of nightmare. He experiences Gothic as terror, Christian aspiration as interfused with alarm. This is intensified by the experience of discovering, in some ‘great folio books’, the ‘unspeakably lovely’ images of the Greek gods – his gods – only to have them inked over by clerical vandalism. The revelation, however, has been ineradicable: ‘the world again began to glow about me. Glooms that brooded over it slowly thinned away’. Hearn later contends that his epiphany of ‘antique beauty’ is not ‘cognition, but…recognition’. ‘You cannot’, he insists, ‘make a Goth out of a Greek’.

In the pattern of external mirroring internal exile, Hearn anticipates Joyce: if Jim steers a course for Tara via Holyhead, Lafcadio heads for Athens by way of Cincinnati. He steeps himself in the counterculture of the river, is drawn inexorably south: to the courtyards of New Orleans, to the islands of the Caribbean, with their Mediterranean colour and light; to ‘purple ports…under a perpendicular sun’. It seems at last that he has found what he has longed for:

this nude, warm, savage, amorous Southern Nature succeeds in persuading you that…the struggle for life in the North…wasted years which might have been delightfully dozed away in a land where the air is always warm, the sea always the colour of sapphire, the woods perpetually green as the plumage of a green parrot’.

However, there is an unexpected reversal:

But when, after all this stupid, brutal, never-varying heat, you steam North, and the constellations change…and the first grand whiff of cold air comes like the advent of a Ghost, – Lord, how one’s brain suddenly clears and thrills into working order.

Now, like the Ulysses he admires in Tennyson, abandoning everything he knows or thinks he knows, Hearn sets sail for an archipelago which presents itself in subtler tones: which gives him, in his own word, shadowings. And, curiously enough, these shadowings converge with the other side of his heritage, that which he may have imagined he had left behind. ‘Japan’, he reports, ‘is chromatically spectral’. He sees himself reflected in the mirror of a Shintō shrine – for which, externally grey and internally empty in a perpetual dusk – he proposes the term ‘ghost-house’ – and wonders if his destiny there is to find himself; the phantom of the sea behind, whether that which he seeks has any external reality. No-one could understand him, a friend observed, ‘who did not take into account his belief in Ghosts…Already, when hardly more than a boy, he begins to talk of heredity – of “the Race-Ghost”’. He begins ‘puzzling over those blind instincts and tendencies, those strange impulses, desires, and memories that well up from unknown deeps within us…To understand him at all it must be understood that Lafcadio Hearn was a mystic…one seeking ever to discern the permanent behind the impermanent; the noumena behind the phenomena’.

iii

This is nowhere more apparent than in his account of the summer dance of the dead: the hypnotic motion of the dancers to the beat of the great drum, muffled by the humid night in which sound and sensation are blurred. Hearn beautifully catches this mood: the sense, not only that the living call to the dead, but that in so doing they seem themselves assimilated to their shadowy condition. More and more unreal, he muses,

this spectacle appears, with its silent smilings, with its silent bowings, as if in obeisance to watchers invisible; and I find myself wondering whether, were I to utter but a whisper, all would not vanish forever, save the grey mouldering court and the desolate temple...

In the scene described by Hearn, then, one might say that the movement of the dance enacts an interweaving of worlds. And this has been described as the central theme of early Irish consciousness: the interaction between the human and the divine; the stepping into an otherworld through the time and space of this one. ‘In pagan Ireland’, states O’Rahilly,

every district of importance tended to have its own síd or hill within which the Otherworld was believed to be located; nevertheless there was in Celtic belief but one Otherworld, despite the fact that so many locations were assigned to it.

The Celtic otherworld, then, is both close and distant, strange and familiar, earthly and ethereal, ultimately unknowable yet intimately known. Write Alwyn and Brinley Rees:

A mist falls upon us in an open plain, and lo, we are there witnessing its wonders. We go to sleep in the enchanted land and by morning all has disappeared, or we have been mysteriously re-transported to our own homes. The limits of such a world cannot be ‘defined’ in terms of distance or direction. Situated far beyond the horizon, it is the goal of the most perilous journey in the world; present unseen all around us, it can break in upon us ‘in the twinkling of an eye’…Defying definition in space, the Other World also transcends mundane time…Many are the stories…which tell of a man who returns after a seemingly brief sojourn in that enchanted world and finds that his contemporaries are dead and that his own name is but a memory. When he touches the ground or embraces a venerable grand-nephew or tastes the food of mortals, he moulders into a little heap of dust as though he had been dead for ages.

Hearn’s apprenticeship for his Japanese voyage, then, was not only aesthetic but atavistic: his ‘Dream of a Summer Day’ echoing the return from the Land of Youth of Macpherson’s Ossian.

But he was not prepared to leave these tales in the realm of myth; he declared them relevant even in terms of the materialism of his time. When he sees the ‘special religious characteristic of Japan’ as an ‘intimate sense of relation between the visible and invisible worlds’, and states that this ‘ancient spiritualism explains the impulses and acts of men as due to the influence of the dead’, he insists that this hypothesis

no modern thinker can declare irrational, since it can claim justification from the scientific doctrine of psychological evolution, according to which each living brain represents the structural work of innumerable dead lives...we cannot honestly deny that our impulses and feelings, and the higher capacities evolved through the feelings, have literally been shaped by the dead, and bequeathed to us by the dead...Figuratively we may say that every mind is a mind of ghosts.

This – what has been described as his ‘evolutional doctrine of organic memory’ – underlies all inner reality for Hearn. ‘The dead’, he declares, ‘are the real seers’; and here, it has been pointed out, Hearn foreshadows Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious, of primordial images or archetypes, of ‘the inherited powers of human imagination as it was from time immemorial’.

Writing when he did, however, Hearn went on to contrast this attitude with that of the world he had left behind:

Of past humanity as unity, – of the millions long-buried as real kindred, – we either think not at all, or think only with the same sort of curiosity that we give to the subject of extinct races.

The single exception he makes is a significant one: the belief in the return of the dead on the night of All Souls; significant because we know it to be continuous with the Celtic festival of the otherworld. With this exception, Hearn characterises the world he had known as lacking in the Japanese feeling towards its ancestors of ‘grateful and reverential love’: of failing to recognise, on the emotional level, ‘the prodigious debt of the present to the past’. For ‘all our knowledge’, he reminds us,

is bequeathed knowledge. The dead have left us record of all they were able to learn...They left us the story of their errors and efforts...they made our world.

The rule of the dead, therefore, extends over the outer as well as the inner world: is indeed the law of the cosmos. All potentialities, Hearn declares,

of life and thought and emotion pass from nebula to universe, from system to system, from star to planet or moon, and back again to cyclonic storms of atomicity...Even as our personal lives are ruled by the now viewless lives of the past, so doubtless the life of our Earth, and of the system to which it belongs, is ruled by ghosts of spheres innumerable: dead universes, – dead suns and planets and moons, – as forms long since dissolved into the night, but as forces immortal and eternally working.

iv

This assertion calls up the great story with which Joyce concludes Dubliners:

His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself which these dead had one time reared and lived in was dissolving and dwindling.

Here is Hearn’s assertion that the dead ‘made our world’, coupled with his sense of universal impermanence. ‘One by one they were all becoming shades’. This recalls that moment in Hearn’s account of the summer dance in which the dancers come to seem unreal to him; and perhaps most evocative of all, when Hearn insists that the dead are the real seers, it is, he says, because the living person ‘is only the visible end of an invisible column of force reaching out of the infinite past into the momentary present, – only the material Symbol of an immaterial host’: Joyce’s ‘vast hosts of the dead’.

This dimension of Joyce’s story interacts with others, all closely woven to intensely dramatic effect. From the moment his protagonist enters the island home of the three Morkan women, he has come within the ambit of the Morrígain, triple goddess of war; and, one after another, in an assault on his psyche, military apparitions press forward on every side. The feast turns into a fight as its dishes, decanters and bottles stand sentry, lie in waiting, are drawn up in squads, or are advanced ‘to the noise of orders and counter- orders’. And, while the company moves to the dance-pattern of lancers, he is assaulted, to the code-word ‘crow’ – ominous manifestation of the war- goddess, as at the death of Cuchulain – by a young woman who wishes to draw him away from his projected journey eastward on behalf of the dominant living languages to one westward into the domain of a dying Gaelic: a summons repeated by his wife, and arbitrarily rejected. But the summons is renewed, and this time surrendered to in terror, when that domain is encountered again in a song, sung in a crow’s voice, that suggests the defeat of Gaelic Ireland at the battle of Aughrim, and that calls up for his wife, to his own obliteration, the spirit of her dead lover.

The scene has meanwhile shifted to a second otherworld location, superimposed over the first. The doomed hero Cuchulain is replaced by the doomed king Conaire: who, as astutely noted by John Kelleher, is equated with Joyce’s protagonist Conroy by the three syllables given his name by the Morkans’ servant. Conaire perishes in the abode of Da Derga, Red God of the otherworld, where the war-goddesses perch on the ridge-pole. At the time of Joyce’s story, remarks Kelleher, the Gresham Hotel, where its dénouement takes place, was of red brick; and the otherworld dwelling is tripled on the route between the other two:

The lamps were still burning redly in the murky air and, across the river, the palace of the Four Courts stood out menacingly against the heavy sky.

The husband is Conroy, suggestive of erotic dominion over his wife; the lover Furey, whose ferocious ascendancy over her spirit proves this to be an illusion. Again, the husband is Gabriel, angel of spring, of the incarnation which stirs humanity with the renewal of life, the lover Michael, angel of autumn, of the fiery sword that bars the way to the lost earthly paradise. And the battle between them has been foreshadowed throughout the story: in the references to William of Orange, who encompassed the final defeat of Celtic Ireland; to his lieutenant Marlborough, who makes a ghostly appearance through the melody of Malbrouck; and to Wellington who, though notoriously born in Ireland, defined it as enemy territory and opposed the national revival under O’Connell. Joyce’s entire narrative, then, in all its thematic complexity, is drawn together in a phrase of Hearn’s: ‘A contest’, he had written, ‘between...two wills is a contest of phantom armies’.

The ultimately defeated O’Connell is seen shrouded in snow; and, in the end, the snow itself becomes ‘general’, nature conspiring to obliterate all of Ireland, to assimilate the world of the living to that of the dead, as Gabriel comes to recognise that all humanity ultimately goes down in defeat. But what is most devastating is, to invoke Hemingway’s phrase, not Gabriel’s defeat but his destruction: the appalling insight that he has never stirred his wife’s imagination as her dead lover did; that he has never been absolutely in love; has never faced death, as his rival did, with that insouciance which is the supreme expression of life; that he has never truly lived.

His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

v

To Hearn, at a distance, Mount Fuji appears otherworldly:

You can seldom distinguish the snowless base, which remains the same colour as the sky: you perceive only the white cone seeming to hang in heaven...seeming to hang, the ghost of a peak, between the luminous land and the luminous heaven.

Yet when he actually makes the ascent of the mountain, he discovers that it is

black, – charcoal black, – a frightful extinct heap of visible ashes and cinders and slaggy lava...always becoming more sharply, more grimly, more atrociously defined.

It is, he declares, ‘a stupefaction, a nightmare’. And so, he concludes,

one of the fairest, if not the fairest of earthly visions, resolves itself into a spectacle of horror and death.

Carl Dawson suggests that Hearn here reverts to ‘theories of the sublime, in which fear and awe compete with a gentler concept of beauty’: that polarity formulated by Burke which echoes the alternations of the Celtic goddess between ghastliness and grace. And Hearn invokes the converse transformation over another sacred peak of Japan: finding Mount Kompira on a grey day ‘common enough’; yet imagining it, under another aspect, as ‘the ascent, through blue light and sungold, into the phantom city’ of the otherworld. By intimations of which he is inescapably possessed:

Today is one of those warm, hushed days when it is possible to think of things as they are, – when ocean, peak, and plain seem no more real than the arching of blue emptiness above them. All is mirage, – my physical self, and the sunlit road, and the slow rippling of the grain under a sleepy wind…

Some Versions of Nothing

Hinduism, notes Jung, has mandalas that are danced. Krishna moves through such a measure in his play of ecstasy: indeed, writes Roxanne Gupta, the rapture ‘invoked by Indian dance might more accurately be called entasy, the inner, blissful state attained through yogic meditation’.

In the stillness at the heart of the dance, where desire is suspended, is an apprehension of wholeness, fused by Yeats with that of alchemy in imagining

That if a dancer stayed his hungry foot

It seemed the sun and moon were in the fruit.

Again, in A Vision, it has been pointed out, ‘The Dance of the Four Royal Persons’ suggests the ‘Royal Persons’ who undergo transformation in The Chymical Marriage of Christian Rosencreutz. In Yeats, these are ‘the King, the Queen, the Prince and the Princess of the Country of Wisdom’: that is to say, male and female, age and youth, compose a quaternity, archetype of wholeness. They are ‘black’, or unconscious in terms of the dominant consciousness, the Caliph who has outlawed the unintelligible; yet they are ‘splendidly dressed’, as befits the numinosity of the archetype, and they insist upon meeting him ‘on the edge of the desert’ – border between cosmos and chaos, consciousness and the unconscious – where at last they prevail over his scepticism.

i

So, once more, in ‘Byzantium’, the ‘golden smithies of the Emperor’ fuse, as locus of transformation, with the sacred space of his pavement

Where blood-begotten spirits come

And all complexities of fury leave,

Dying into a dance,

An agony of trance,

An agony of flame that cannot singe a sleeve.

This is glossed in A Vision:

I think of a girl in a Japanese play whose ghost tells a priest of a slight sin, if indeed it was sin, which seems great because of her exaggerated conscience. She is surrounded by flames, and though the priest explains that if she but ceased to believe in those flames they would cease to exist, believe she must, and the play ends in an elaborate dance, the dance of her agony.

The play embodies a tradition steeped in Buddhism, the priest is a Buddhist priest, the doctrine Buddhist doctrine. How can we square this with its vehement rejection in ‘The Statues’? Another instance of Yeats’ continuing ambivalence? Of, as a dedicated astrologer, knowing himself to have been born under the sign of Gemini, those twins that alternate between earth and heaven, consciously elaborating what Helen Vendler refers to as his ‘agonising balance between opposites’? Perhaps. Denis Donoghue declares that ‘the best way to read Yeats’ Collected Poems is to think of it as dramatising a great dispute between Self and Soul’.

ii

Ramesh Chandra Shah, accordingly, concludes that Yeats’ ‘relationship with the “solutions of the east”’ was ‘dialectical’, ‘a creative and life-giving conflict’; but he puts the question on another plane by suggesting that both aspects of Yeats’ dilemma are accounted for by the Hindu metaphysics of Māyā, as expounded by Heinrich Zimmer. On the one side, it is ‘the delirium of the manifested forms’, ‘the creative joy of life’; on the other, it is ‘the supreme power that generates and animates the display’ of these forms; and, Zimmer goes on,

regarding the bafflements of Māyā as utterly real, we endure an endless ordeal of blandishment, desire and death; whereas, from a standpoint just beyond our ken (that represented in the perennial esoteric tradition and known to the illimited, supra-personal experience of ascetic, yogic experience) Māyā…is as fugitive and evanescent as cloud and mist. The aim of Indian thought has always been to learn the secret of the entanglement, and, if possible, to cut through into a reality outside and beneath the emotional and intellectual convolutions that enwrap our conscious being.

Harbans Rai Bachchan argues that unambiguous acceptance of such a metaphysic would have stricken the poet dumb:

But one small knot-grass growing by the pool

Sang where – unnecessary cruel voice –

Old silence bids its chosen race rejoice.

A similar thought occurs in Buddhism; and here, too, the ambivalence Yeats reflects is to be found in his sources. In the centuries after the Buddha’s enlightenment, his teaching was transmitted on the understanding that he was a pragmatist who took no interest in, and implicitly denied, the existence of a permanent self or soul; liberation therefore was detachment from all that is passing, including the personality – even that of the Buddha – and from his teaching, which was merely a means to that end. This extinction of desire, nirvāna or blowing-out, was not thought of as annihilation, since there was not believed to be anything permanent to annihilate. Such, in this view, was the Buddha’s emptiness.

However, over the same centuries, modifications of these doctrines appeared, which coalesced into the Buddhism which called itself Mahāyāna, the greater vehicle, and the other Hīnayāna, the lesser. Where the so-called Hīnayāna ignored or denied any being behind appearances, Mahāyāna posited one which was absolute. Of this, the historical Buddha was seen as a manifestation, and the nirvāna aspired to by his followers as its realisation in themselves: the extinction of apparent personality in favour of immanence. Emptiness now takes on a very different connotation; and it is this which is bodied forth in the Noh.

iii

The revelation famously came in definitive form to Yeats through what has been described as ‘a “secret society” of modernism’: his association with Ezra Pound over the Japanese notebooks of Ernest Fenollosa. Fenollosa hailed from Salem, Massachusetts, which traded with Asia; and it was through local connections that he found himself in Japan, and fascinated by its arts. He apprenticed himself to the hereditary practitioners of the Noh, and prepared translations of its texts; he studied Chinese poetry with a Japanese scholar who went through them word by word and character by character: a procedure of which he kept a conscientious record. These were the notebooks his widow gave Pound to edit; and it is not too much to say that they remade English writing.

Fenollosa had served as consultant to the art patron Charles Lang Freer, whose gallery stands on the Mall in Washington, and who was both a collector of the work of Whistler and a close friend; and Whistler told him that the Japanese prints which had influenced him so comprehensively were merely a faint intimation of an ancient and profound tradition. Pound held Whistler in reverence, seeing him as an artist who had struggled for an individual style. But what mattered most for Pound was that he struggled for a style that was specifically national: as the title of his poem, ‘To Whistler, American’, makes clear; and in this provided inspiration.

iv

How could imitation of Japan be seen as expressive of America? The answer is to be found in a Whistler etching of Battersea Bridge. Here, while the high curve of the structure comes from the woodblock print, the space surrounding it derives from the older genre of ink painting: which Whistler had exceptional opportunities of seeing. For the etching is dated to a time in which Japanese artists were demonstrating its techniques at a Paris exposition where Whistler exhibited.

This use of space came from Sung China, and that version of Buddhism known as Ch’an or Zen; and this in turn derived from the deepest intuitions of Indian thought. While mathematics elsewhere might conceive of nothingness as a blank, in India it was apprehended as a reality, the term for which, shūnya, or ‘void’, when filtered through Arabic and Italian, give ‘cipher’ and ‘zero’: ‘that refined creation’, asserts Spengler,

…which, for the Indian soul that conceived it…was nothing more nor less than the key to the meaning of existence’.

‘For the Hindus’, explains Robert Kaplan,

there is no unqualified nothingness…fullness – brahman – pervades the universe, and…the ‘absolute element’ that plays a similar role in Buddhism…is empty (shūnya) only of the accidental.

In the relevant version of Buddhism:

All is shūnya, void, empty, as all realities are disclaimed. Thus, whatever is, is not describable by any concept. Being devoid of any phenomenal characteristics, ‘void’ or ‘the indescribable’ is the real nature of things.

This is formulated in the Sanskrit text which asserts:

rūpān na prthak shūnyatā shūnyatāyā na prthag rūpām;

form is not different from emptiness, nor emptiness from form.

Or, in the Sino-Japanese version central to Zen:

shiki fu i kū kū fu i shiki.

v

This is what Whistler encountered in the Zen tradition of painting. Here, against the depth of water, mist or sky are set down mountains, trees and fishing-boats: with, writes Sherman E. Lee, ‘extremely bold “flung-ink” techniques, as drastically simple as a sword cut or an explosion…a pictorial parallel to the mystic’s sudden enlightenment’. And this aesthetic was reproduced with what has been called ‘astonishing completeness’ in Japan. Here, however, it was carried further; here, it has been observed, splashes of ink on white paper are transposed into rocks on white gravel: paintings metamorphose ‘into meditation gardens…devoid of foliage and water…making them into deeper statements of Zen Void’.

It was in this feeling for space that affinity was found. ‘American craft’, writes Hugh Kenner in his masterly book The Pound Era, ‘works by structure, not accretion, and an American poetic is unembarrassed by open spaces… (hence Whistler’s and Fenollosa’s hospitality to an oriental aesthetic of intervals)’.

vi

As space is to substance, so is silence to speech. Ishibashi Hiro, in her study of Yeats and the Noh, says that among the striking features of that drama’s music ‘are its sense of tension, of silence…This “silence” should… enable one to feel immense depth and a sense of infinity…as space does in… painting’.

As space to substance, so silence to speech; and this too has roots deep in religion. The Greek word ‘mystery’ has been traced to a cognate of Latin ‘mute’; and throughout mystical literature are intimations that ultimate reality is beyond language. Says Eckhart, Gott ist namenlos: nameless in the sense of indescribable. Divinity, asserts Eriugena, nihilum non immerito uocitatur: ‘is not unreasonably called “Nothing”’ – that is to say, no thing, nothing that can be spoken of. Plotinus cites from Plato the statement that supreme being can neither be spoken of nor written about: oude rhēton oude grapton. In the Hindu scriptures, the concept is pervasive, as when Arjuna is instructed by Lord Krishna: avyakto ’yam acintyo ’yam avikāryo ’yam ucyate; the spirit is avyaktah – invisible, avikāryah – unchanging, and acintyah, incapable of being thought.

This philosophy of the unspoken is equally prominent in Buddhism, being most characteristically expressed in China and Japan through Zen, which traces itself to an original silence. In the words of Yeats:

Do you remember the story of Buddha who gave a flower to some one, who in his turn gave another a silent gift and so from man to man for centuries passed on the doctrine of the Zen school?

vii

And it was from this part of the world that it was transmitted to Ezra Pound. In a note to that lament of a forlorn lover, ‘The Jewel Stairs’ Grievance’, he observes: ‘The poem is especially prized because she utters no direct reproach. We note also that the poet, Li Po, is given his Japanese name Rihaku, thereby acknowledging that the Chinese verses had come to him along that route. This phenomenon is even more obvious in ‘Fan-Piece, for Her Imperial Lord’, where Pound takes a ten-line translation from a scholarly volume, and condenses it into three, brilliantly evoking the common fate of fan and poet – being set aside – in the single word ‘also’. Here, it has been noted, Pound’s reworking of the Chinese takes a Japanese shape; and in fact he had had numerous opportunities of acquaintance with haiku, that sparest of poetic forms. As for its spirit: ‘All things’, explains D. T. Suzuki, ‘come out of an unknown abyss’; and any one of them can give a glimpse into that abyss when rendered with the most sparing of brushstrokes: for Suzuki explicitly links haiku with Zen painting: both using a minimum of ink to achieve a maximum of space or suggestibility.

viii

Pound so wielded the technique of omission in the manuscript of The Waste Land that Eliot dedicated it to him as the greater poet. That is to say, Pound deepened the poem’s silences. He performed a similar service for a young journalist who arrived in Paris from the battlefield determined to write about it. His writing thus far was conventional, inflated and abstract; Pound helped to change that. In what has been described as Hemingway’s ‘college education’, he worked his way through a reading-list provided by the poet. It may be difficult to imagine Hemingway poring over Eliot; nevertheless, he did so. ‘Reading The Waste Land with Ezra Pound at one’s elbow’, suggests his biographer Michael Reynolds, ‘is no bad way to pick up a thing or two’.

So much was this so that the characteristic technique of Hemingway’s stories has been described as ‘The Thing Left Out’. He was candid about this. ‘I always try to write’, he declared, ‘on the principle of the iceberg. There is seven-eighths of it underwater for every part that shows’. What gives the writing depth, however, is the quality of its space. ‘Anything you can omit that you know’, he insists, ‘you still have in the writing and its quality will show. When a writer omits things he does not know, they show like holes in his writing’.

Pound was not the only writer then in Paris whose influence may be traced in Hemingway. Above all there was Gertrude Stein, whose studio apartment Hemingway remembered, with its ‘great paintings’, as being

like one of the best rooms in the finest museum except that there was a big fireplace and it was warm and comfortable and they gave you…natural distilled liqueurs made from purple plums, yellow plums or wild raspberries…whether they were quetsche, mirabelle or framboise they all tasted like the fruits they came from, converted into a controlled fire on your tongue that warmed you and loosened it.

Stein, however, remembered Hemingway more as a listener than a talker; and some idea of what he might have listened to may be gauged from a letter her brother Leo had written long before. Leo Stein had been to Japan and collected its woodblock prints, and gone on from there to Toulouse-Lautrec, in whom he perceived their influence, and others, especially Cézanne, of whom it was said that his landscapes would ‘leave out a great deal’, yet ‘be more meaningful than the original scene’, build up a picture ‘out of omissions’, of which the blank areas were ‘the unstatable core’. Leo Stein concluded:

There can scarcely be such as thing as a completed Cézanne. Every canvas is a battlefield and victory an unattainable ideal.

It is a principle which echoes throughout Hemingway’s oeuvre, from the first intimations of his vocation to its fulfilment. He declared, in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech,

For a true writer each book should be a new beginning where he tries again for something that is beyond attainment.

And his alter ego had confessed long before:

He, Nick, wanted to write about country so it would be there as Cézanne had done it in painting…You could do it if you would fight it out.

ix

What Hemingway picked up along the boulevards, however, was scarcely more than an elaboration of what had come to him from the battlefield. On the day his first war ended, the American was thrown in with an Irish officer in the British army who, noting a combat decoration akin to his own, struck up an acquaintance. The relationship quickly turned to hero-worship on Hemingway’s side, as he discovered in Eric Dorman-Smith an officer who, in contrast to his own ambulance service, was a poised Sandhurst survivor of decimation in the trenches. When Hemingway showed him a draft of ‘Big Two-Hearted River’ – that tale of trauma in a war left undescribed – which indulged in psychological reverie, and he suggested ‘that the chap had better catch some more trout and leave Freud to the intellectuals…I was surprised’, says the soldier, ‘that he took the piece, tore it up and began again’. As Hemingway stated: ‘I have decided that all that mental conversation…is the shit and have cut it all out…I’ve finished it off the way it ought to have been all along. Just the straight fishing’.

Dorman-Smith’s influence is already apparent in those anecdotes of his which Hemingway incorporated into in our time. Robert Graves recalls that there were some in that war for whom the usages of chivalry still prevailed: who fought the king’s enemies impersonally, without animosity. A similar attitude informs Dorman-Smith’s appreciation of his own adversaries – ‘Their officers were very fine’ – and the nonchalance with which he alludes to danger: ‘We were frightfully put out when we heard the flank had gone, and we had to fall back’. Huizinga in Homo Ludens connects battle, not only with play but with ritual, and so with the realm of the sacred. When Nick Adams, then, refers to writing as combat, his aesthetic takes on a metaphysical dimension:

He felt almost holy about it.

In the words of the Nobel laureate,

he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.

Hemingway, it has been noted, is the artist as hero, for whom the fight is a metaphor. If true experience transcends intellect, it transcends language: what cannot be thought cannot be told; or, if so, only by suggestion and with great difficulty. Writing, then, for Hemingway, is a wrestling with inarticulacy, a facing down the void.

x

A like sensibility informs his association with the bullfight. This, he insists, is not a sport, but a tragedy – that is to say, an artform:

Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death and in which the degree of brilliance in the performance is left to the fighter’s honour.

He illustrates this with a pair of pictures of the same fighter in the same pass. Of the first he says:

The emotion is given by the closeness with which the matador brings the bull past his body;

and of the second:

with the danger removed man and bull do not form one group but are separate entities.

Here again the criterion is space; and what defines the space is the tension inherent in it. The same was true of his stories: ‘it was the tension Hemingway valued’, writes Julian Smith, ‘not the Thing that caused the tension, so he left the Thing out’.

Unlikely as the collocation may appear, D. T. Suzuki, in his book Zen and Japanese Culture, having defined the connection between Zen and the way of the warrior as fearlessness in the face of death, illustrates his point by reference to a bullfighter, Juan Belmonte, whom Hemingway had seen at Pamplona and described in The Sun Also Rises. The account Suzuki quotes is prefaced by the assertion, again, that bullfighting ‘is not a sport’; it ‘is an art…its emotion is spiritual’. And, as the Japanese fighter loses the conception of ego in the moment of battle, Belmonte is quoted as saying:

As soon as my bull came out I went up to it…I heard the howl of the multitude rising to their feet. What had I done? All at once I forgot the public…myself, and even the bull; I began to fight…as precisely as if I had been drawing a design on a blackboard. They say that my passes…that afternoon were a revelation of the art of bullfighting. I don’t know…I’m not competent to judge. I simply fought as I believe one ought to fight, without a thought outside my own faith in what I was doing.

xi

A comparable attitude appears in the poem Yeats wrote as he in turn faced death:

Know that when all words are said

And a man is fighting mad,

Something drops from eyes long blind,

He completes his partial mind,

For an instant stands at ease,

Laughs aloud, his heart at peace.

Even the wisest man grows tense

With some sort of violence

Before he can accomplish fate,

Know his work or choose his mate.

xii

Modernism, like Romanticism and Aestheticism, is scarcely comprehensible apart from the influence of Asia; and Yeats, it might be argued, encompasses all three. He is Romantic in ‘Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland’, with its naturalist ‘brown thorn-tree’; he is Aesthetic in ‘Sailing to Byzantium’, with its artefact of the ‘golden bough’; and he is Modernist in ‘Lapis Lazuli’, with its invisible ‘plum or cherry-branch’.

Influence, it goes without saying, is a far cry from identity: as no two spaces are alike, neither are any two silences. There is a world of difference between those who have nothing to say and those for whom there is nothing to be said. Strangers and lovers.

Métaphysique Nocturne

In the ancient Japanese capital of Nara, the temple of Tōdaiji houses a gigantic image of gleaming black. This records the moment in which Buddhism, travelling through China and Korea from India, was formally adopted as the state religion. Amid concern about disloyalty to indigenous tradition, the imperial sun-goddess revealed in a dream that she and the foreign deity were one and the same. So it is that the image is of the solar Buddha Vairocana.

Another dream, another synthesis: this time in the writings of Magonus Sucatus Patricius, alias St. Patrick. Patrick, it has been pointed out, is the earliest person recorded to have become more Hibernian than the Hibernians. ‘They despise us’, he thunders, ‘for being Irish’: ‘they’ being the British amongst whom he was born, and ‘us’ the people with whom he had come to identify. Patrick, however, looks forward still further into Irish literature. He records a dream of paralysing oppression which he dissipated by calling out ‘Helias!’: a word which has been explained as a conflation of the Hellenic sun-god Helios and the Hebrew prophet Elias, the latter being assimilated to the former through his ascent to heaven in a fiery chariot. If Patrick, then, anticipates Yeats in his pride of Anglo-Irishry, he anticipates Joyce in his punning dreamworld of Finnegans Wake.

Among the multiple layers of allusion in that title is ‘Finn Again Wakes’, referring to the eternal resurrection of Finn or Fionn, the Celtic sun-god who has left his name in such locations as Swiss Windisch, French Vendresse and Vienne, and the capital of Austria; and Patrick is no less concerned than the Buddhists of Japan to assimilate the foreign to the indigenous, defining his belief as worship of ‘the true sun – Christ’: solem uerum Christum.

i

So it was that, in a synthesis parallel to that of Japan, the impulses of Celtic religion were absorbed into Christianity, and nowhere with more sophistication than in the figure described as ‘one of the greatest metaphysicians of all time’. In an age when Irish scholars quit their homeland, then under attack by the Vikings, for libraries and lecture-halls abroad, he was taken into the palace of the king of France; and, to lend distinction to the commonplace ‘John of Ireland’, Johannes Scottus devised for himself, on a Vergilian model, the more resonant ‘Of Origin in Éire’, Eriugena.

If, as his contemporaries come into closer focus, he is no longer quite ‘the loneliest figure in the history of European thought’, he is still seen, in the words of Helen Waddell, as ‘head and shoulders above’ them: ‘head and shoulders, some hold, above the Middle Ages’. Yeats indeed finds in him ‘the last intellectual synthesis before the death of philosophy’ – the death, that is to say, of the ‘spiritual and abstract’ at the hands of the ‘animal and literal’.

In some ways he is still very close to us. We can touch the pages on which his ‘spontaneous and impulsive’ handwriting has been identified; and we can hear him think in his own language when he glosses biblical terms with the Old Irish equivalents of buachaill, ruadh, teach, déanamh, gealt, faoileáin – ‘herdsman’, ‘red’, ‘house’, ‘making’, ‘crazy’, ‘seagull’ – while the continuing potency of Celtic myth appears in his rendering of Isaiah’s demoness as Morrígain, the dark deity who presides as a crow over the death of Cuchulain and the destruction of Gabriel Conroy.

ii

One of the centres associated with Eriugena is what has been called the crowned mountain of Laon, its pierced towers silhouetted against the sky high above the surrounding plain. This is appropriate: for, like Lyons, Leiden and elsewhere, its name has been traced to Lugdunum, fortress of Lugh, double of Fionn as light-god; and light is the core of Eriugena’s philosophy.

It has indeed been described as ‘in a way, the whole of his thought’: since for Eriugena all being is ‘a theophany of light’; or, in his own words, Omnia, quae sunt, lumina sunt: ‘all things that are are lights’. The translation is that of Ezra Pound, who in exploring medieval thought uncovered the Eriugenian dictum, imagined he found it echoed in China, and so juxtaposed his name with the Chinese ideogram which connotes brightness through the combined images of sun and moon. The result has been described as ‘magnificent misreading’: for, as so often with imaginative error, it contains an intimation of truth. A parallel may indeed be found in that Chinese form of Buddhism known as Ch’an, Son or Zen, where the seeker of enlightenment is asked: ‘Do you smell the mountain laurel?’ ‘Yes’. ‘There’, says the master, ‘I have held nothing back from you’.

iii

In a book cited in the library scene of Ulysses, d’Arbois de Jubainville contends that Eriugena clothes ‘in the forms of Greek philosophy’ the ancient Celtic pantheism he discerns in the Song of Amairgen:

I am wind on sea,

I am ocean wave,

I am roar of billows,

I am bull of seven fights,

I am hawk on cliff,

I am tear of the sun,

I am fairest of flowers,

I am boar for valour,

I am salmon in pool,

I am lake on plain,

I am height of art,

I am word of skill,

I am point of spear,

I am god who fashions fire in the head.

In this connection, Alwyn and Brinley Rees cite the Bhagavad-Gītā:

I am the dice-play of the cunning:

I am the strength of the strong…

I am the silence of things secret:

I am the knowledge of the knower.

Eriugena was in fact cited in support of pantheism some centuries later, and his work condemned at Rome. This would scarcely have surprised him. Among the apostles, the Celtic Church, like the Greek, felt a closer affinity with the mystical John than the administrative Peter; and Eriugena was scathing on the contrast. On the statement of his namesake that ‘the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it’, he comments:

Peter is proposed as the model of action…whereas John follows the model of contemplation. The former often floundered…For action…sometimes…clouded over with carnal thoughts, is deceived. But the glance of profound contemplation, once it has penetrated to the face of truth, can never be beaten back, can never be deceived, can never be blinded by any darkness: nequaquam repercutitur, nunquam fallitur, nulla caligine occultatur in perpetuum.

There was a very curious aftermath. William of Malmesbury records a tradition that Eriugena ended his days in his own abbey, stabbed to death with their metal styli by his students because, it is alleged, he made them think. After he had been buried in the chapel where he was murdered, the story goes on, a heavenly light impelled the transfer of the body to the main church, where an inscription lauded his sanctity. In recognition of which, he was listed in the Roman Martyrology; but, when his writings were printed, the saint was once more found to be anathema.

iv

However, by this time his influence had radically altered the face of Europe. The best-known story about Eriugena is of the King of France asking him what distanced an alcoholic from an Irishman – Quid distat inter sottum et Scottum? – and his reply, ‘The table’: Tabula tantum. The lasting significance of the tale is that it indicates easy relations between them; and out of these came the event that altered his life. For Charles asked him to translate into Latin a gift from the Emperor of Byzantium, the Greek text of the anonymous author who called himself Dionysius.

In taking this name, he had assumed the identity of the Dionysius converted by Saint Paul in Athens, so securing the cachet of Christianity for a mystical philosophy which represents, it has been said, ‘the supreme holiness and beauty of light’. And, as filtered through Eriugena, it was to manifest itself in most extraordinary fashion in France.

For Dionysius had a peculiarly intimate significance there. Legend installed him as bishop of Paris, martyred on the hill subsequently known as Montmartre and buried at the royal abbey of St.-Denis. Here it was that philosophy took visible form. In Suger, St.-Denis found an abbot who served also as regent of France, an administrator as likely to provide a winepress as a prior, and a scholar who ranged from anecdotes out of French history to recitations of Latin verse. All these roles combined in the conviction that his abbey, which housed the tombs of the ‘Apostle of all Gaul’ and its monarchs, was the symbolic centre of the kingdom, and in the action he took to glorify it. This he justified by paraphrase of Eriugena. The latter, commenting on Dionysius, had declared:

The material lights, both those which are disposed by nature in the spaces of the heavens and those which are produced on earth by human artifice, are images of the intelligible lights, and above all of the True Light Itself: materialia lumina, sive quæ naturaliter in cælestibus spatiis ordinata sunt, sive quæ in terris humano artificio efficiuntur, imagines sunt intelligibilium luminum, super omnium ipsius veræ lucis.

From this Suger derived the verses:

being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten…minds…that they may travel…through…true lights…

To…True Light:

opus quod nobile claret

Clarificet mentes, ut eant per lumina vera

Ad verum lumen.

The work in question was Suger’s recreation of the church at St.-Denis so that it embodied, from the glow of a rose window at one end to the shifting luminescence amid a forest of columns at the other, what has been called ‘the first great monument of the Gothic style’.

v

Eriugena’s philosophical system, like that of Dionysius, is framed by a twofold process, divisio and resolutio: ‘the process by which the unmanifest God becomes visible’ in creation, and ‘the return of all created things to their source’. In this, Dionysius had founded himself on Neoplatonism; and Neoplatonism in turn, as formulated by Plotinus, has been found to have had antecedents elsewhere.

For Plotinus studied at Alexandria, on the trade-route between the Mediterranean and India. In the one direction flowed silks, spices and ivories; in the other, wine, glass and silver; in both, people and their ideas. Embassies from India are recorded as having reached Roman emperors including Augustus, Trajan, Hadrian, Constantine and Julian. A statuette from Pompeii is of a type also found in India; Pliny, who perished in the eruption that buried the city, sets a high value on trade with that land. A Greek sailing-manual gives detailed directions for getting there; and Catullus evokes the echo of breakers along the Indian coast:

litus ut longe resonante Eoa

tunditur unda.

The Tamil texts of the south have admiring accounts of the beautiful ships of the yavanas, or Ionians, described as ‘valiant-eyed’ and much in demand as mercenaries, whose names are found on Indian shrines. In the north, meanwhile, in the wake of Alexander’s incursion, Greek monarchs issued coins bearing Hindu trident or Buddhist wheel; and the Socratic dialogue which recounts the conversion of one of them, The Questions of King Milinda, or Menander, is a classic text of Buddhism. A Greek ambassador to an Indian court provides a detailed account of Hinduism. Alexander had brought back with him a philosopher who immolated himself at Susa, an exploit repeated by another Indian at Athens: episodes so well known that St. Paul can speak without explanation of giving one’s body to be burned. India, indeed, was a staging-post for places further afield: Horace and Vergil speak of the Chinese as Sēres, silk people; and a Roman mosaic in Tunisia illustrates yin and yang. Alexandria had a resident Indian community; and here too have been discovered images of trident and wheel. Dion Chrysostom, who speaks of Indians in his Alexandrian audience, describes an epic that sounds like the Mahābhārata. Clement of Alexandria alludes to the ‘Boutta’ as a teacher who had acquired divine status. It has even been suggested that the epithet of Plotinus’ instructor at Alexandria, Ammonius Saccas, represents the Sanskrit shākya, or Buddhist.

vi

It is scarcely astonishing, then, that correspondences should have been traced between Plotinus and Indian thought. He describes an object as being ‘all faces’ (pamprosōpon); ‘shining with living faces’ (lampon zōsi prosōpois): images for which it would be difficult to find antecedents in Greece, but which evoke vividly the many-faced sculptures of India. He employs this image to show how the One of divinity becomes the Many of the world; and in his account of the return of the Many to the One shows no less affinity with Hinduism. His merging of the individual in the absolute, writes Émile Bréhier, is foreign to Hellenic philosophy. Where Plato affirms the transcendence of the One, to be apprehended in the madness of ecstasy – described by Bréhier as ‘a bond of external dependence’ between One and Many – Plotinus finds immanence also: for him, the ‘soul discovers the One within its inmost depths’; as do the Upanishads.

Plotinus, also, belongs to the tradition of apophasis, for which the absolute is indefinable. For him, awareness of the One is ‘not by way of reasoned knowledge or of intellectual perception…but by way of a presence superior to knowledge’: kata parousian epistēmēs kreittona. It is the tradition in which speech is superseded by silence; and in Dionysius this is analogous to the supersession of light by darkness. Divinity, he holds, is made manifest only to those who leave behind ‘every divine light, every voice, every word from heaven, and who plunge into the darkness where…dwells the One who is beyond all things’.

vii

The same holds true for Eriugena: as there is a darkness below light, so there is a darkness above. In what has been described as his métaphysique nocturne, Deirdre Carabine writes, ‘God can be understood as darkness because of God’s transcendence, yet this…is really…an ineffable light that simply appears dark’: being beyond the reach of the mind. In Eriugena’s own words:

Cujus lux per excellentiam tenebrae nominatur, quoniam a nulla creatura, quid vel qualis sit, comprehenditur.

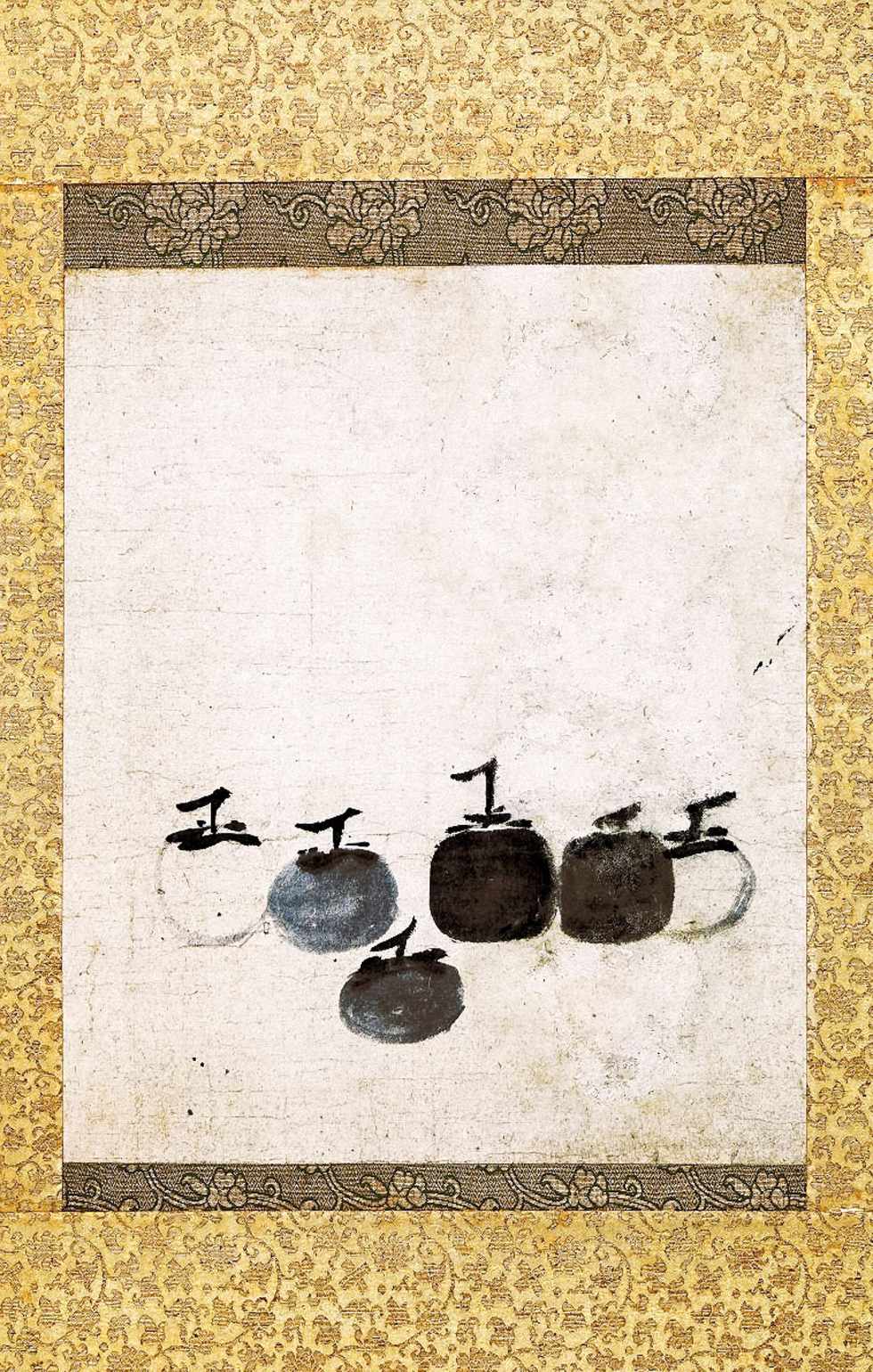

For Zen, also, the ultimate reach of enlightenment is represented by images of darkness. The celebrated painting of persimmons by Mu Ch’i, in which the six pieces of fruit are seen as allegorising the stages of that process, is dominated by the central specimen, which has been described, appropriately, as ‘lampblack’. Likewise, the ‘last transcendence’, states Dumoulin, ‘the final freedom which the Zen masters attribute to enlightenment’, is symbolised by a black circle.

Eriugena’s great masterpiece, the Periphyseon or De Divisione Naturae, ends with an anticipation of ‘that light which will turn to darkness the “light” of those who falsely philosophise, and to light the “darkness” of those who truly know’: ille lux, quae de luce falso philosophantium facit tenebras, et tenebras recte cognoscentium conuertit in lucem. He had written of the One ‘Who is better known by not knowing, of Whom ignorance is the true knowledge’: qui melius nesciendo scitur, cuius ignorantia uera est sapientia. Likewise, a patriarch of Zen, when asked how he had attained his position, replied: ‘Because I do not understand Buddhism’. In the words of the Kena Upanishad: ‘those who know not, know; those who know, know nothing at all’:

yasyāmatam tasya matam matam yasya na veda sah.