SHARAWADGI

The Romantic Return

to Nature

by

Ciaran Murray

International Scholars Publications

An Imprint of Rowman and Littlefield

THE mysterious sharawadgi, or asymmetry of the Romantic garden, has long intrigued historians. Here Ciaran Murray locates its origin in Japan, and follows its trajectory from the Dutch trading-post at Nagasaki to Temple, British ambassador at The Hague and patron of Swift. For Swift’s friend Addison, the irregular garden symbolised the liberty of nature invoked in the English revolution. In its cosmological implications, it fused with the findings of Galileo, bringing the dynamic universe of the Tao to bear on the surrealist vision of Swift and the unlimited vista of the Romantic elysium. Sharawadgi became the leitmotif of the English eighteenth century, underlying the subversive natural liberty of Walpole’s Gothic and Gibbon’s Germans, until its appearance in the French revolution induced the return to order of Burke. Ciaran Murray’s narrative unfolds with the immediacy of a novel – except that it is actual, and dramatically alters the landscape of intellectual history.

Preface

‘Some years ago, on a winter evening, as I watched the light fade on Mount Leinster from Oak Park, near Carlow, it was borne in upon me that the darkening lake in the middle distance, with its woods and its island, was as deliberate a creation as the Roman archway through which I had entered. I had lately come from Entsuji, in Kyoto, where the dark trunks of the cryptomeria frame the pale slopes of Mount Hiei in a geometrical arrangement; and for a moment I saw one in terms of the other. Each appeared to function on the principle of shakkei, or borrowed landscape, being built around the view of a distant mountain.

I spoke of this to Robert J. Smith, of Cornell, who sent me to the rare book cage of the Olin Library, and to Sirén’s China and the Gardens of Europe of the Eighteenth Century, where I learned of the Asian antecedents of the English landscape garden; and, as I read on into the subject, this came to seem a fundamental notation for the eighteenth century. I have attempted, therefore, to record the phenomenon, from its discovery and domestication at the beginning of the century to its strange disappearance, or transformation, at the end.’

Introduction

‘The sequence is coherent and irrefutable. The Restoration diplomat William Temple wrote a spellbound account of the gardens of the “Chineses”. The Queen Anne essayist Joseph Addison held these up as a pattern for England. The Georgian poet Alexander Pope put Addison’s programme into practice. But to state this is only to pose further questions. Temple does not merely supply exotic information; he confers prestige upon it. This would seem to imply a certain originality of perception. Addison does not rest content with paraphrase; he urges adoption of the alien schema. This would seem to indicate a certain boldness of thought. Pope does not simply concur; he builds, we are told, a “setting that expressed him” out of the creation of a man that he hated. This would seem to involve a certain paradox.

Here is the tale of three men and an idea; and none of these three, as conventionally understood, can have done what he did.’

Chapters

PART I: THE TREE OF LIFE: Origins of Romanticism

- The Case of the Fastidious Envoy. Temple, British ambassador to the Netherlands, then the only European country in contact with Japan, identifies the principle of nature in Taoist government and the invisible order of the Sino-Japanese garden.

- The Fireworks Night of Joseph Addison. Addison, finding in the second a metaphor for the first – as seen in the English revolution – initiates Romanticism.

- Fair Thames and Double Scenes. An achievement concealed under the inconsistent and incoherent fabrications whereby Pope has contaminated the sources of intellectual history.

PART II: THE TREE OF KNOWLEDGE: Implications of Romanticism

- The Singular Demon of Doctor Bentley. All the above unfolds against the recent astronomical validation of the unlimited universe posited in antiquity, which gives contemporary relevance to Temple’s identification with Epicurus, and induces metaphysical vertigo in his secretary Swift.

- The Spacious Firmament on High. But exhilaration in Swift’s friend Addison.

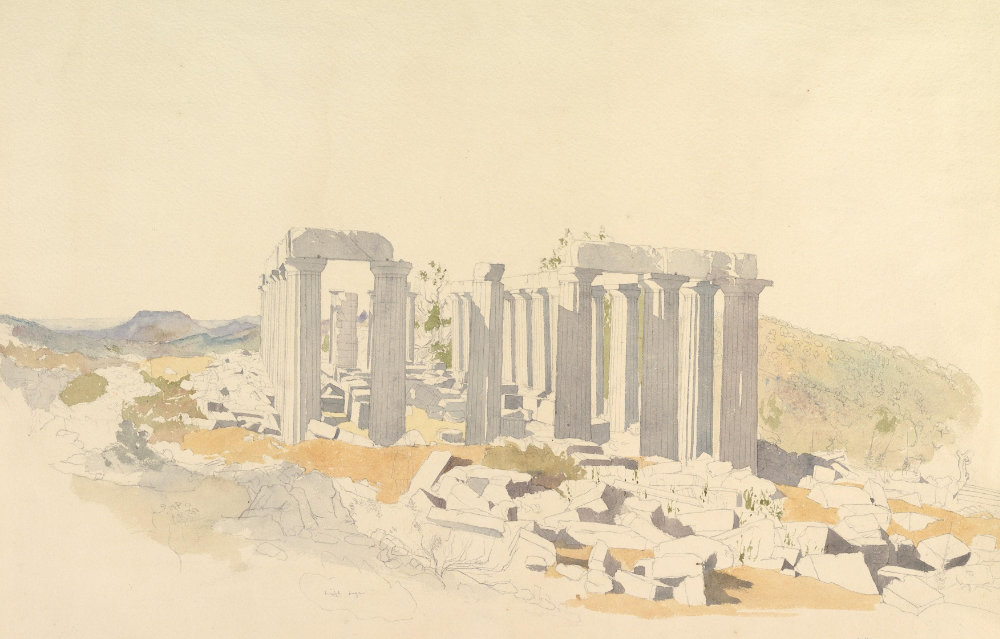

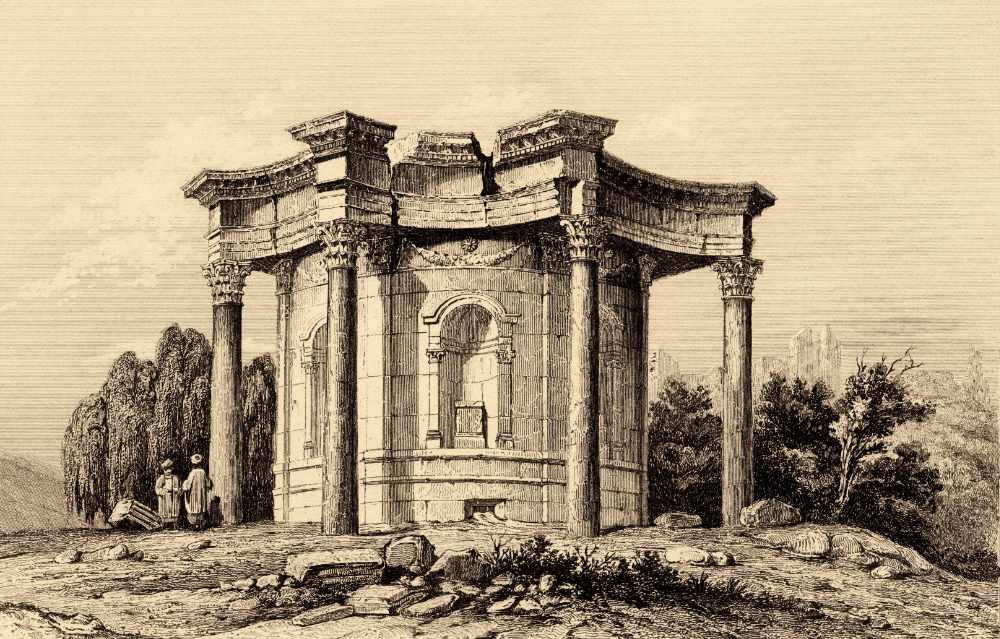

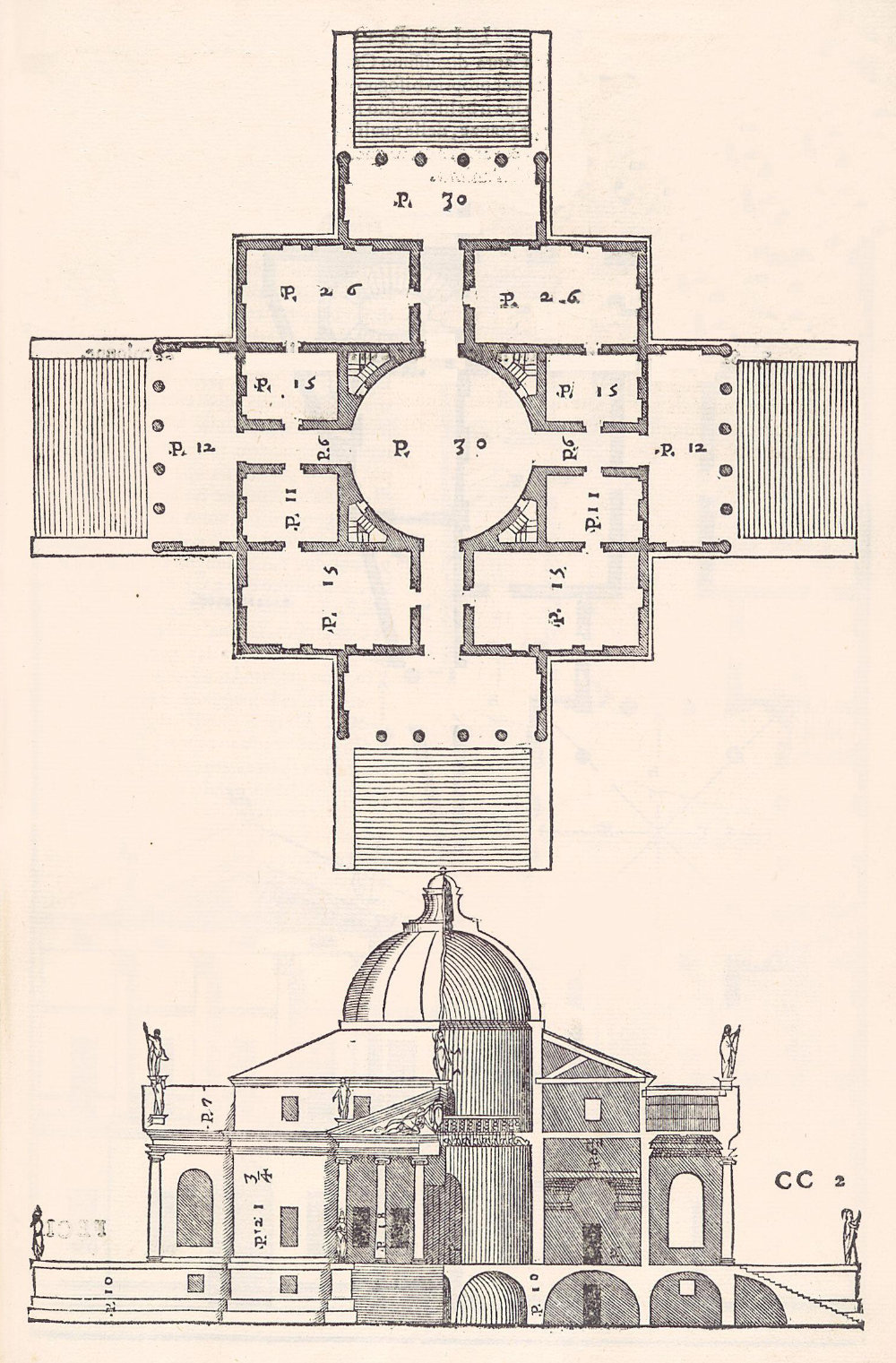

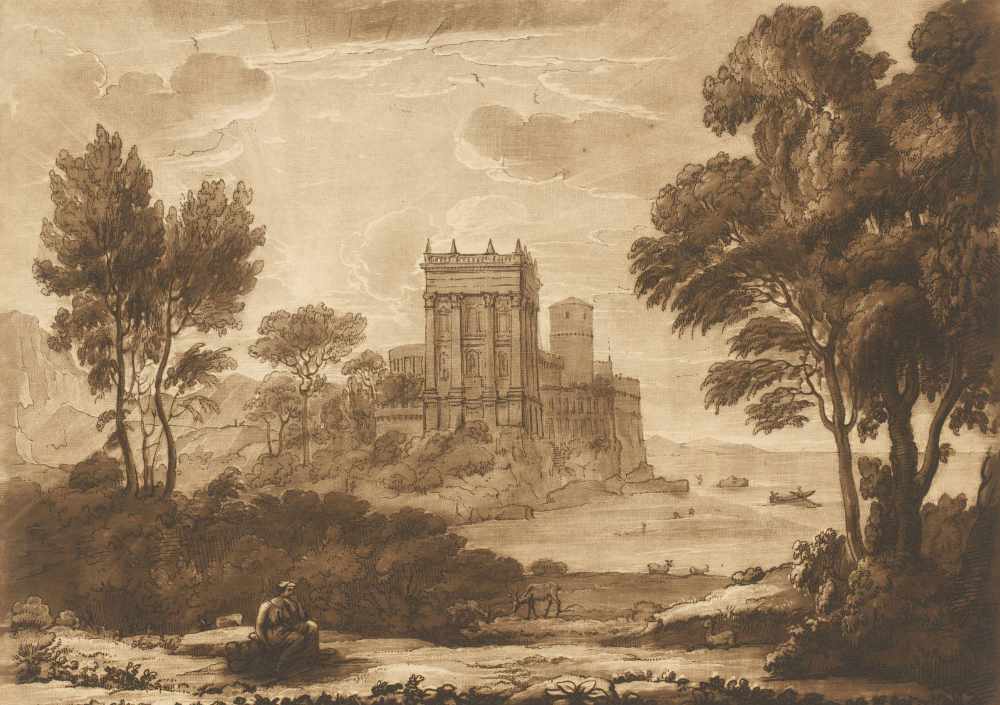

- Il Riposo di Claudio. And inspires the infinite vistas of Claude Lorrain: whose combination of these with classical architecture provides the blueprint for the English landscape garden; restoring in this the sacred landscape of antiquity.

PART III: IMPERIAL PARADISE: Ramifications of Romanticism

- The Garden Invades the House. Horace Walpole revives the Gothic style in the name of sharawadgi, the Japanese word signifying asymmetry cited by Temple in relation to the naturalist principle of the Sino-Japanese garden.

- The Eternal Moment. As it is again by Gibbon when he contrasts Gothic dynamism with the stasis of declining Rome: so formulating the central metaphor of the English eighteenth century as Germanic by origin and Roman by achievement.

- A Vista to the Gallows. By the same token, the French revolution seemed an assault on an aristocratic paradise to him, Walpole and Burke: the last of whom initiated the nineteenth-century formula whereby Gothic building became an image of the growth of institutions through time – and so, like the classical, conservative – while the garden returned to formality.

‘Sharawadgi traces the history of English landscape design to the decentralised gardens of Japan. The author covers the romantic period during the eighteenth century, and the key personalities of William Temple, Joseph Addison and Alexander Pope. Murray explores the psychological subtleties of these men as well as the interchange between East and West. A fascinating read for students of Asia or English romanticism’ – www.amazon.com

‘Lucid and masterful...an important book’ – Seamus Deane, Dublin.

‘Ciaran Murray’s monumental Sharawadgi...quietly revolutionises our understanding of eighteenth-century intellectual history...One senses an energy and tension in Murray’s own journey, a great personal and psychic quest to unravel the truth of this most important historical transition in human feeling’ – Peter McMillan, Journal of Irish Studies, Tokyo.

‘Murray...reviews, with trenchant and illuminating commentary, a succession of the leading eighteenth-century personalities and key events in the fields of landscape, literature, art, architecture, philosophy, politics, science and religion...Sharawadgi: The Romantic Return to Nature should be read by serious students not only of garden history, but also of eighteenth-century culture in general...Murray’s impressive scholarship is enlivened by wit and the sheer quality and sparkle of the writing’ – Peter Hayden, Garden History, London.

‘Impressionistic...sharing much in tone with Lytton Strachey and...Edward Gibbon’ – Donald Richie, Japan Times, Tokyo.

‘Sharawadgi in itself – unusual and beautiful – this book is truly remarkable: rigorous, brilliant, vivid’ – Dimitri Shvidkovsky, Bulletin of the Journal of Decorative Art, Moscow.

‘A readable, new, fascinating, tautly-argued account of the influence of Japan on Romanticism’ – Pádraig Ó Snodaigh, Irish Times, Dublin.

‘The...word “sharawadgi” might as well be “shazam” for all of the power that Murray has invested it with...but what sets this scholarly book apart from the others on the shelf is its companionability and charm’ – Charlie Canning, Kansai Time Out, Kobe.

‘In-depth research’ – Lei Gao & Jan Woudstra, Shakkei.

‘Great book’ – Marilyn Gaull, The Wordsworth Circle, New York.

Sharawadgi Agonistes

Act I

Under the bam

Under the boo

Under the bamboo tree

T. S. ELIOT

When an excerpt from my book Sharawadgi appeared in Garden History, its then editor described its argument as ‘convincing’.1 However, in a later issue, Wybe Kuitert asserts the opposite, alleging that my reflections on the ‘meaning and origin of the term Sharawadgi…lack conviction’: the reason given being that they ‘do not consider seventeenth-century sources’.2

As stated, this is unsustainable. Five of the nine chapters in my book have to do with the seventeenth century; all cite contemporary sources. Prof. Kuitert, on the other hand, provides no evidence for his assertion, merely referring us to ‘Wybe Kuitert, “Japanese art, aesthetics, and a European discourse: unraveling Sharawadgi”: which, we are assured, is to be found in ‘Japan Review (International Research Center for Japanese Studies, Kyoto), 26 (forthcoming)’. That might be difficult: Japan Review 26 was already in print, and Prof. Kuitert’s article was not in it. Nor would one expect it to be: it is a special issue devoted to erotic prints (shunga).

Kuitert’s reading of sharawadgi as a combination of share (‘refinement’) and aji (‘taste’) is not original: I have cited the suggestion that this was conflated with shorowaji (‘not being regular’). The case that Prof. Kuitert has to meet if he omits the latter is the existence of a word which not only means what Sir William Temple said it meant, but has been triangulated with the time and location of the Dutch settlement in Japan.3 That this should be coincidence seems incredible; but as we shall see, Prof. Kuitert expects us to believe still more extravagant propositions.

The question is not addressed in the essay Prof. Kuitert credits with having ‘inspired’ him, Makoto Nakamura’s ‘Sharawadgi ni tsuite’. This is a brief and avowedly tentative introduction to the subject; and, for what it is worth, since published in 1987 was unavailable to me when in 1980 I began the dissertation (on the ‘Intellectual Origins of the England Landscape Garden’, 1985) which underlies my book.4 At that time, and indeed for some time afterwards, a major obstacle to identifying sharawadgi as Japanese was a general belief among historians of architecture and the garden (with the formidable support of Sir Nikolaus Pevsner) that it was Chinese. That is what Temple seems to say, and what I had to explain: which I did by referring to – yes – seventeenth-century sources.5

Here again Prof. Kuitert puts forward an alternative: ‘In England, after war with the Dutch, it was deemed safer to distance oneself from these drunken and profane merchants living on an “indigested vomit of the sea”’. But if Temple was intimidated by prejudice against the Dutch, why is so much of his writing taken up with sympathetic accounts of them?6 However, Prof. Kuitert goes on: ‘Neither did Temple want to associate his deviation from the classics of Vitruvius’ – sic – ‘by referring to something as light-hearted as a robe from Japan… Temple was impressed by Chinese statesmanship and Confucianism; these were the things he liked to associate with his understanding of sharawadgi’. This is not original either;7 and the conspiracy theory bound up with it seems both implausible and superfluous. Implausible, because it does not explain some of the facts; superfluous, because all of them can be explained without it. Here is what Temple wrote: ‘And whoever observes the work upon the best India gowns, or the painting upon their best skreens or purcellans, will find their beauty is all of this kind (that is) without order’.8 If China is camouflage for Japan, why drag in India? The most natural reading, it still seems to me, is that Temple speaks of Asian design in general: a contention I have supported from – yes again, I am afraid – seventeenth-century sources, including a visitor to Temple’s house and a book he is known to have read, in terms of which ‘India’ includes China and Japan, and the two latter are interchangeable.9

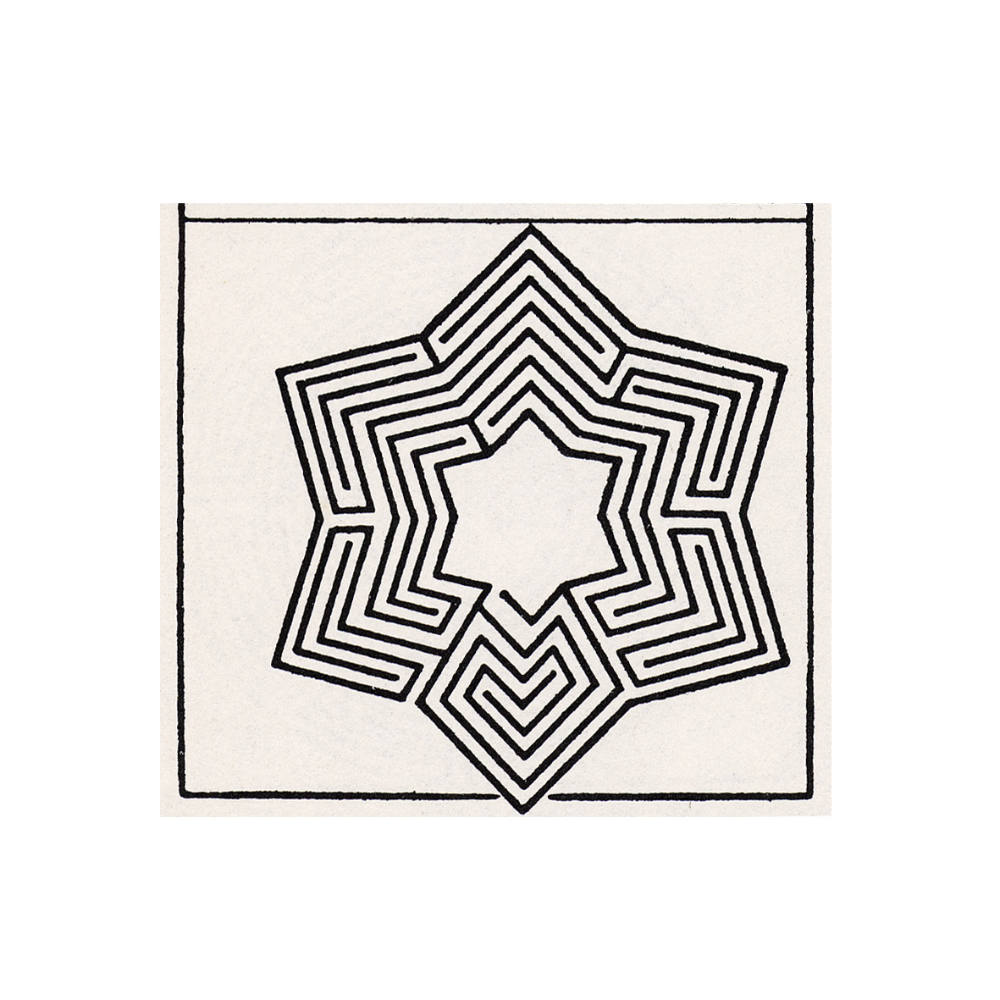

What is in principle novel and to be welcomed is an attempt to expand the Dutch context for Temple’s information which has long been acknowledged by those who accept a Japanese origin for the term.10 This Prof. Kuitert does through consideration of Constantijn Huygens, providing a plan of his garden – which, however, shows it as uncompromisingly geometrical. Prof. Kuitert nevertheless insists that the area within the ‘blocks’ was ‘planted asymmetrically with trees, as in an Italian bosco’. This hardly proves Japanese precedent: limited irregularity was standard in the baroque garden, and both Temple and Addison had seen examples;11 what was different about sharawadgi was that it involved asymmetry as its central principle: in Temple’s phrase, gardens ‘wholly irregular’.12

Prof. Kuitert cites Huygens on the asymmetrical designs that adorned Japanese clothing; but this is hardly indicative of support for them.

- I ended up with the unequal of the Japanese robe

- The incomprehensible of its staining so bewildered

- That makes the dress a decoration, but makes me ill at ease;

- And if I would happen to to tread such paths,

- Me thinks it would be like a gamble, or whatever,

- Where this tree would stand, or where that path would end.

- I would be discomfited, and where I came to turn,

- There would my head be turning, just like the planter did

- Who carelessly had everything diverged from its correct position.13

This sounds like a satire on sharawadgi, or at least a sense of being dizzied by it; and Prof. Kuitert provides no better evidence to the contrary than an assertion that the kimono, since it was symmetrical in shape though asymmetrical in pattern, ‘fitted precisely what Huygens was aiming at in his garden with its symmetric blocks of wilderness’. To describe this as unconvincing would scarcely do justice to the jugglery whereby a document is called in evidence for its diametrical opposite. And, in the end, Prof. Kuitert concedes of Temple: ‘Strikingly, he elevated lack of order to the level of a taste in beauty, whereas for Huygens the discussion was not much more than a kind of explanatory apology for a design idea’ – if it was that.

Prof. Kuitert further informs us that, in giving his essay the title ‘Upon the Gardens of Epicurus’, Temple alluded to ‘a non-biblical, classical philosophy’. He did a great deal more, if we are to trust the seventeenth-century sources in which ‘the arguments of Epicurus had returned with new and terrible force’, consequent on the discovery by Galileo of an asymmetrical universe. I have devoted some space to this, and its linkage with the worldview of the Tao, as it affected Temple and Addison, as well as Temple’s secretary and Addison’s friend, Swift.14 It seems to me that if we are to account for the reception of sharawadgi in England, we must attempt to explain how the individuals responsible could have felt affinity with it.

All of this Prof. Kuitert glosses over, merely following his mention of Epicurus with the assertion: ‘Temple referred to classicists such as Horace and Varro as his teachers on the fruit garden, although all his fruits were imported from the Continent’ (sic). Even what he grew beside the Thames?15

- I may truly say, that the French, who have eaten my peaches and grapes at Sheen…

- have generally concluded, that the last are as good as any they have eaten in France, on this side Fontainebleau; and the first as good as any they have eat in Gascony…

- Italians have agreed, my white figs to be as good as any of that sort in Italy.16

I suppose I should not blame Prof. Kuitert for misrepresenting what I have written when he has failed to read properly the document on which he proposes to set me right.

Prof. Kuitert ends at the point where Addison assimilates Temple’s information; but the genius of Addison was that he transformed it by means of a general aesthetic that fed into Romanticism. I have sketched something of this;17 but no more imagined I had said the last word than the first: ‘So large a canvas made imperative that impressionism which, Butterfield has observed, is the inevitable effect of ellipsis: “the selection of facts for the purpose of maintaining the impression – maintaining, in spite of omissions, the inner relations of the whole”’.18 By implication, one might envisage any number of further investigations. I have myself attempted something of this kind in a subsequent volume, tracing sharawadgi and its sequels through the lens of Irish literature.19 A similar volume from a Dutch perspective might prove useful; meanwhile, Prof. Kuitert has adduced nothing to alter the conviction – tends, if anything, to intensify it – that what matters about sharawadgi is what happened to it in England.

Act II

And calm of mind, all passion spent

JOHN MILTON

In ‘Re-solving Sharawadgi: Some Thoughts on its Chinese Roots’, Lei Gao & Jan Woudstra wonder whether there is not after all a Chinese source for sharawadgi:20 disagreeing with me, one might say, in most agreeable fashion. They suggest, accordingly, a possible solution in shīyihuajing 詩意畫境 or shīqinghuayi 詩情畫意, ‘poetic and picturesque emotions’; and go on to expatiate on ‘how the Chinese appreciated the beauty of nature as seen through their gardens’; on how deeply they loved ‘these landscapes and the philosophy embedded in them’. Here they preach to the converted: nobody with even the most cursory knowledge of the Chinese landscape tradition would question its subtlety and depth;21 I have pointed out, moreover, that the gardens of Japan were continually influenced by those of China, and Temple was aware of the similarity. A book he is known to have read shows a naturalistic Chinese garden, with pine-trees, waterfall and jagged stonework; and he knew, too, that the Chinese imperial palace was surrounded by ‘large and delicious gardens’, containing ‘artificial rocks and hills’.22

However, the authors say of Chinese nature poetry that ‘there is no reference to irregularity, nor does it mention anything being irregular’. Precisely: the naturalistic irregularity that struck Temple so forcibly derived from his coming from a tradition in which gardens were overwhelmingly geometrical. One does not argue that Temple was versed in the inner meaning of the Sino-Japanese tradition; the whole point of his account, and its historical importance, derives from his having been an outsider with an altogether different world-view. Methodologically, therefore, one has to say that Temple’s lack of schooling in the intricacies of the Sino-Japanese landscape tradition not only does not detract from his observations, but constitutes their worth: a reaction of awed surprise that nevertheless is willing to acknowledge value in this exotic way of doing things.

Further points of methodology that arise include the following concession by the authors:

While checking the database of Si Ku Quan Shu (The Complete Library of Four Treasures), the biggest collection of Chinese books before the 18th century, it appears that the four characters shī yi hua jing 詩意畫境 were not used together in written language, however there are hundreds of examples where shī yi 詩意 (spirit of poem) and hua jing 畫境 (picturesque scenery) are used to describe an admirable quality of a painting or landscape. Additionally shīqinghuayi 詩情畫意 (poetic beauty; picturesque scenery) as a single phrase appeared twelve times, which was first used by the Chinese several centuries before Temple, as an expression of their sentiment towards a landcape.

One must observe, then, that in common with previous attempts to find a Chinese equivalent for Temple’s term, shīyihuajing is not ‘supported by actual usage’; while shīqinghuayi, like these earlier proposals,23 sounds a great deal more remote from sharawadgi than the Japanese shorowaji.

The authors attempt to meet this objection by appealing to Cantonese, in terms of which they propose ‘si-ji-wa-ging’ for shīyihuajing, ‘si-tsing- wa-ji’ for shīqinghuayi, and ‘si-wa-ji-ging’ for shīhuayijing 詩畫意境 (‘poetic and picturesque landscape or conception’). To this reader, ‘si-ji-wa-ging’, ‘si-tsing-wa-ji’ and ‘si-wa-ji-ging’ still sound very distant from sharawadgi; and, though we are told that in ‘the 17th century most European visitors…lived in areas of Southeast China such as Macao and Canton’, we are not informed as to any connection Temple may have had with them. His connection with people who had visited Japan, on the other hand, is a matter of record.24 As I have observed, though Temple

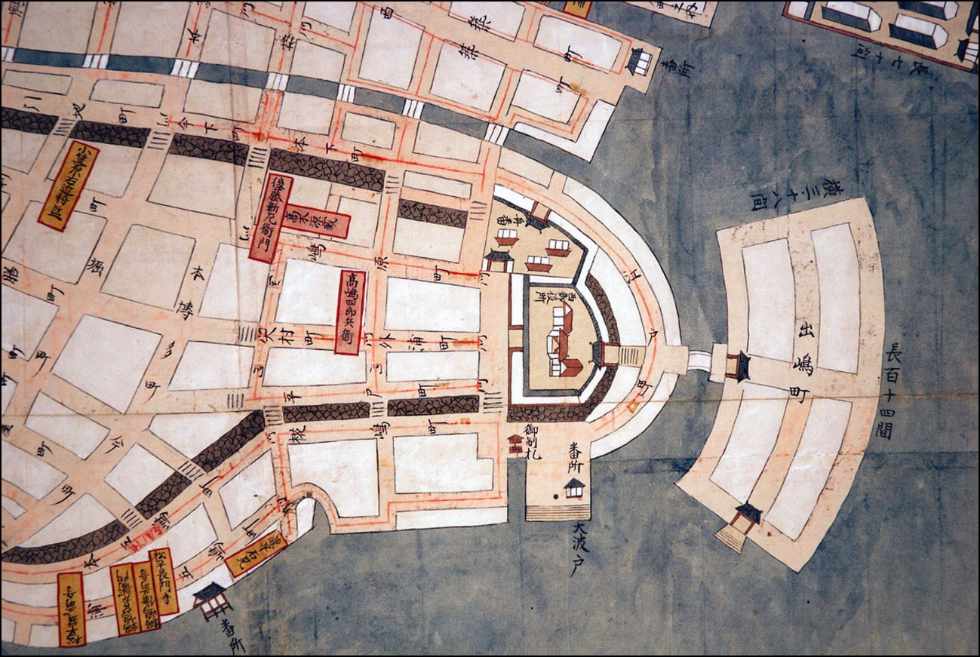

was aware from his reading that Chinese gardens were irregular…on those of Japan he had access to more privileged information. For he was accredited to the one country in Europe to which Japan was still open by trade; that trade was conducted through Djakarta by the Dutch East India company; and it was with that company that, in his trade negotiations in Holland, he had had to deal.25

The authors, to their credit, do not insist on their hypothesis; and one is unwilling to engage in controversy with research which admits its limitations with such candour, and whose allusions to the present author are phrased with such courtesy, the result being a model of civilised dissent. All I would do, then, is recapitulate my reasons for suggesting what I did: i) Temple’s contemporaries regularly interchanged China and Japan; ii) he was aware that the gardens of the two were similar; iii) he had met Netherlanders who had served in Japan; iv) the usage shorowaji points to the time and place of the Dutch settlement; v) it indicates asymmetry, as Temple said it did;26 vi) we are informed that knowledge by the Dutch in Japan and their Japanese interlocutors of each other’s languages was far from perfect; vii) so that, if conflated with the Japanese words share and aji (‘refinement’ and ‘taste’), shorowaji covers all of Temple’s claims for it.27

A question raised in the course of the article involves the issue of priority: ‘A paper published by Takau Shimada one year before Murray’s thesis… suggested that…the word would better have been translated as sawaraji (or sawarazu or their derivatives), which means “let’s not touch”, “let things as they are”. This solution provides a different angle of understanding oriental gardens, which appreciates nature as art’.28 My reply to this is that I became aware of it only after my book had been published; and that, once I had, it still seemed to me that shorowaji was closer both to sharawadgi and to Temple’s context of ‘gardens wholly irregular’.

However, to dispose of the question of priority once and for all, let me state that my first publication on the subject had been twenty years previously, when in 1978, at the request of a colleague at Shizuoka University, I published an account of the ongoing research which was to issue in the dissertation of 1980-85 alluded to above.29 This article, ‘Kyoto and the Origins of English Romanticism’,30 was distributed elsewhere in Japan; and, as I was informed by the colleague responsible, stimulated considerable interest in the subject. Here I cited the suggestion that sharawadgi represented the Japanese shorowaji made in 1931 and 1934 by E. V. Gatenby,31 a member of the Asiatic Society of Japan, and supported in 1968 by another member, Ivan Morris. I myself, as I have acknowledged, was introduced to the subject by yet another member, Robert J. Smith.32 This to get the question out of the way: it seems to me that, if there is to be any credit assigned for priority, it belongs properly to Gatenby.

What I attempted was to offer solutions to the difficulties created by Gatenby’s hypothesis. Of these, two stand out. The first, outlined above, is Temple’s citation of his source as ‘Chinese’. The second, which had even more formidable support at the time I wrote, was the contention that sharawadgi, whether Chinese or Japanese, was irrelevant to the naturalism of the English landscape garden. This derived ultimately from Pope’s declaration, a year after Addison, paraphrasing Temple, had made a pioneering proposal in this regard, that he, Pope, had found the principle in the European classics, rendering Asian influence superfluous. A large part of my dissertation was taken up with unravelling the relentless process of deceit, including a fabricated correspondence with Addison which reversed their respective roles, and which so imposed upon subsequent opinion that, at the time I wrote, whole books were still devoted to this proposition. I remain grateful to the eminent Popean who approved my arguments without alteration, so making it possible to appreciate once more the contribution of Addison and Temple to making sharawadgi known in Europe, with the result that we know as Romanticism.33

A condensed version of the dissertation became the first six chapters of the book, with the last three tracing Temple’s contrast of regular and irregular design in Walpole (classical versus medieval architecture),34 Gibbon (eastern versus western Roman empire)35 and Burke (French versus English constitution).36 Meanwhile, a series of conference papers, later given journal publication, offered previews of its findings: making these available a long time before its publication.37

The subject, then, is one of extraordinary richness, sharawadgi and its sequels having transformed, not only the landscape of Europe but its consciousness. The tracing of sharawadgi as naturalistic irregularity through Temple, Addison, Walpole, Gibbon and Burke would seem to verify this understanding of the term in the course of its being absorbed into the English tradition; and, once it had been, the story as I saw it was complete in outline. I must leave it for others to elaborate.

Epilogue

‘Take off your shoes!’ he said.

‘You bring the problems of the world inside’

TAN TWAN ENG

I like to visit Kyoto every year; but having failed to on one occasion, went in the intercalary days after Christmas. As always, I tried to combine familiar places with vistas not seen before: though sometimes the one can turn into the other.

Given the season, all was quiet; by the same token, the weather was variable. Instead of the blaze of sunlight that points up the rock islands at Ryōanji, the overcast shed a uniform tone on the unshadowed gravel, and it was possible to locate the one spot from which the lines of force in the composition could be apprehended as a whole. Then suddenly the sun emerged, picking up the gleams in the quartz; and the light, instead of being over the garden, appeared to come out of it.

NOTES

- Ciaran Murray, Sharawadgi: The Romantic Return to Nature (Bethesda, MD: International Scholars: an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield, 1999); Garden History, XXVI (1998), 114, 208-13.

- Wybe Kuitert, ‘Japanese Robes, Sharawadgi, and the Landscape Discourse of Sir William Temple and Constantijn Huygens’, Garden History, XL (2013), 157-76.

- Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 37-8, 273-5.

- The question of priority is dealt with more fully below.

- Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 33-5.

- pp. 15, 25.

- pp. 145-7, 300.

- p. 34.

- pp. 33-5, 274.

- pp. 35, 37-8, 274-5.

- p. 273.

- pp. 32-3.

- sic.

- Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 131-66.

- p. 15.

- Sir William Temple, Works, 4 vol. (London: J. Clarke et al., 1757), III, 218-19.

- Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 71-2, 78-9.

- p. ix.

- Ciaran Murray, Disorientalism: Asian Subversions, Irish Visions (Tokyo: Asiatic Society of Japan), 2009.

- ‘Re-solving Sharawadgi: Some Thoughts on its Chinese Roots’, by Lei Gao & Jan Woudstra, Shakkei: The Journal of the Japanese Garden Society, XVII: 1 (2010), 2-9.

- pp. 150-51.

- Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 35, 274.

- pp. 273-4.

- pp. 34-8, 273-5.

- p. 35.

- That naturalistic asymmetry is Temple’s subject can scarcely be disputed: ‘What I have said, of the best forms of gardens, is meant only of such as are in some sort regular; for there may be other forms wholly irregular that may, for aught I know, have more beauty than any of the others; but they must owe it to some extraordinary dispositions of nature in the seat, or some great race of fancy or judgment in the contrivance, which may reduce many disagreeing parts into some figure, which shall yet, upon the whole, be very agreeable. Something of this I have seen in some places, but heard more of it from others who have lived much among the Chineses; a people, whose way of thinking seems to lie as wide of ours in Europe, as their country does. Among us, the beauty of building and planting is placed chiefly in some certain proportions, symmetries, or uniformities; our walks and our trees ranged so as to answer one another, and at exact distances. The Chineses scorn this way of planting, and say, a boy, that can tell an hundred, may plant walks of trees in straight lines, and over-against one another, and to what length and extent he pleases’.

- Temple goes on immediately from the passage cited in note 26: ‘But their greatest reach of imagination is employed in contriving figures, where the beauty shall be great, and strike the eye, but without any order or disposition of parts that shall be commonly or easily observed: and though we have hardly any notion of this sort of beauty, yet they have a particular word to express it, and, where they find it hit their eye at first sight, they say the sharawadgi is fine or is admirable, or any such expression of esteem. And whoever observes the work upon the best India gowns, or the painting upon their best skreens or purcellans, will find their beauty is all of this kind (that is) without order’ (Temple, Works, III, 229-30; this does not differ from the original edition except for such alteration in usage, or idiosyncrasy of the individual printer, as ‘Indian Gowns’ for ‘India gowns’, the latter as in ‘China tea’: Sir William Temple, Miscellanea: The Second Part, London: Simpson, 1690, pp. 57-8 of the garden essay; OED, s. v. China, India). Temple’s last sentence makes it clear that he is thinking of Asian design in general; as was a visitor to his house, who also went ‘to visit our good neighbour, Mr. Bohun, whose whole house is a cabinet of all elegancies, especially Indian; in the hall are contrivances of Japan screens… The landscapes of the screens represent the manner of living, and country of the Chinese’ (John Evelyn, Diary, ed. William Bray, 2 vol., London: Dent, 1952, II, 173, 275: 30th July 1682, 24th March 1688). Again: ‘Half a century later, the interior of a ‘Chinese House’ at Stowe would be described as ‘Indian Japan’ (Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 34-5, 274).

- Citing ‘Is sharawadgi derived from the Japanese word sorowaji?’, Review of English Studies, XLVIII (1997), 350-52.

- Ciaran Murray, ‘The Hollow Tree: Intellectual Origins of the English Landscape Garden’, National University of Ireland, 1985.

- Jimbun Ronshū, ‘Studies in the Humanities’, XXIX, 1978, 1-15.

- E. V. Gatenby, ‘The Influence of Japanese on English’, Studies in English Literature (Tokyo), XI (Oct. 1931), 508-20; ‘Sharawadgi’, Times Literary Supplement 1672 (15 Feb. 1934), 108. Hadfield in 1960 remarked that sharawadgi, ‘though opinions differ, is probably not a Chinese word, but of Japanese origin’; and Honour in 1961, while he spoke of sharawadgi as ‘either Chinese or Japanese’, proposed the Netherlands as Temple’s source (Miles Hadfield, Gardening in Britain, London: Hutchinson, 1960, p. 177n.; Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie: The Vision of Cathay, London: Murray, 1961, p. 145; Murray, ‘Hollow Tree’, p. 407; Sharawadgi, p. 274).

- Douglas Moore Kenrick, A Century of Western Studies of Japan: The First Hundred Years of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 1872-1972, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Third Series, XIV (1978), 293-4, 411, 439; Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. ix, 274.

- Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. x, 81-126..

- pp. 194-6.

- pp. 230, 237-8.

- pp. 250-53.

- Including ‘Swift’s Mentor, Japan and the Origins of Romanticism’, Kobe, 1989: The Harp, Tokyo, V (1990), 1-21; ‘The Japanese Garden and the Mystery of Swift’, Kyoto, 1990: International Aspects of Irish Literature (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe, 1996), pp. 159-68; ‘Anglo-Dutch and Anglo-Irish: The Politics of Romanticism’, Leiden, 1991: The Literature of Politics, The Politics of Literature, 5 vol. (Amsterdam & Atlanta: Rodopi, 1995), I, 23-31; ‘Poor Dick Steele: Catalyst of Romantic Thought’, Tokyo, 1991: The Harp, VII (1992), 1-22; ‘Chiaroscuro: The Infernal Image of William Temple’, Éire: Irish Studies, Tokyo, XI (1991), 60-72; ‘The Dublin M.A. of Samuel Johnson: Unlocking the Code of Romanticism’, Dublin, 1992: ‘Fashion as Fascism: Swift and the Lost Romantics’, Éire, XIV (1994), 79-87; ‘Edmund Burke and Sharawadgi: The Japanese Origin of a Metaphor’, Tokyo, 1993: The Harp, IX (1994), 39-50; ‘The First Romantic: William Temple’, Eigo Eibei Bungaku: English Language & Literature, Chuo University, Tokyo, XXXIV (1994), 329-39; ‘The Second Romantic: Joseph Addison’, Eigo Eibei Bungaku, XXXV (1995), 417-25; ‘Pope and Anti-Pope: Addison’, Eigo Eibei Bungaku, XXXVI (1996), 229-39; ‘The Golden Bough and Sharawadgi: Byzantium in Gibbon and Yeats’, Long Island, 1996: ‘The Golden Flower of Byzantium’, Éire, XIX (1999), 119-29; ‘The Japanese Dawn of Romanticism’, Chuo University, 1996: ‘Towards the Japanese Sunrise: A Celtic Pilgrimage’, Éire, XVII (1997), 90-101; ‘Pope and Anti-Pope: Atticus’, Eigo Eibei Bungaku, XXXVII (1997), 225-34; ‘Murder in the Garden: Addison, Atticus and the End of Romantic Japan’, Eigo Eibei Bungaku, XXXVIII (1998), 253-63; ‘Sharawadgi Resolved’, Garden History, XXVI (1998), 208-13; ‘Sharawadgi: The Japanese Source of Romanticism’, Tokyo, 1999: Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Fourth Series, XIII (1998), 19-34; ‘The Japanese Source of Romanticism’, Grasmere, 2000, The Wordsworth Circle, XXXI: 4 (2000), 176; XXXII: 2 (2001), 106-8.

Sharawadgi Resolved

Garden historians have long been intrigued by the mysterious sharawadgi invoked by Sir William Temple to describe the irregular gardens of the ‘Chineses’; yet no agreement has been reached on his source. This paper demonstrates that the solution has been available for many years, but that its true nature was disguised by the ambiguity of Temple’s language.

The main attempts at a solution were brought together by S. Lang and Nikolaus Pevsner in ‘Sir William Temple and Sharawadgi’, published in The Architectural Review in 1949.1 They open with the statement from the Oxford English Dictionary that the word is ‘of unknown origin’. ‘Chinese scholars agree’, the OED continues, ‘that it cannot belong to that language’.2 This Lang and Pevsner term ‘rather defeatist’, and they go on to cite two attempts to match the word with Chinese. Y. Z. Chang, in ‘A note on sharawadgi’ (1930), suggested sa-lo-kwai-chi, which he glossed as the ‘quality of being impressive or surprising through careless or unorderly grace’. However, in 1940 C. S. Ch’ien contended that this would mean no more than ‘graceful and magnificent’, and proposed instead san-lan-wai-chi, or ‘space tastefully enlivened by disorder’.3 Neither, however, is supported by actual usage; and Lang and Pevsner, agreeing that both are unsatisfactory, devote much ingenuity to the argument that the word was Temple’s invention. This seems defeatist indeeed, particularly as in 1931 E. V. Gatenby had suggested that sharawadgi derived from the Japanese sorowaji, or ‘not being regular’.4 This Lang and Pevsner dismiss as not being Chinese. Nevertheless a number of writers, including P. Quennell in 1968, have subsequently opted for the Japanese solution.5Temple considered the gardens of Europe as mere mathematics; while those of the ‘Chineses’ involved a most subtle aesthetic. He wrote:

Among us, the beauty of building and planting is placed chiefly in some certain proportions, symmetries, or uniformities; our walks and our trees ranged so as to answer one another, and at exact distances. The Chineses scorn this way of planting, and say, a boy, that can tell an hundred, may plant walks of trees in straight lines, and over-against one another, and to what length and extent he pleases. But their greatest reach of imagination is employed in contriving figures where the beauty shall be great, and strike the eye, but without any order or disposition of parts that shall be commonly or easily observed: and, though we have hardly any notion of this kind of beauty, yet they have a particular word to express it, and, where they find it hit their eye at first sight, they say the sharawadgi is fine or is admirable, or any such expression of esteem.6

Sharawadgi, clearly, is the key to Temple’s source; but no Chinese equivalent has been established for it. Instead the suggestion has been made that it stands for the Japanese sorowaji: which in sound and sense – ‘not being regular’ – would correspond to Temple’s word. There is, however, one apparently insurmountable objection to this hypothesis. Temple speaks, unequivocally as it would seem, of the ‘Chineses’: a fact that looms across the path like the towering precipice of a Chinese landscape.

The context of the geography of Temple’s century – at the back of which still lurked the ill-defined notion of the ‘Indies’ – may provide a clue to the problem. ‘By the name of India’, declared one contemporary, ‘we comprehend all that tract between India…on the west…unto China eastward’; while another, still more generous, described as ‘Indian’ plants both from Barbados and Japan.7 Yet another of Temple’s contemporaries achieves a certain magnificence in his ambiguities. ‘Went’, records John Evelyn, ‘to visit our good neighbour, Mr. Bohun, whose whole house is a cabinet of all elegancies, especially Indian; in the hall are contrivances of Japan screens… The landscapes of the screens represent the manner of living, and country of the Chinese’.8 Is ‘Japan’ used here in its sense of lacquer, though the screens are Chinese: Chinese japan, as one might speak of Japanese china? Or are they in fact Japanese, though depicting, as Japanese artists commonly did, Chinese landscapes?9 We cannot tell, and it scarcely matters: because Evelyn, before setting out his eastern wares, unfolds them from a wrapping of ‘Indian’ fabric. And Temple, in a similar context, makes the same equation: ‘And whoever observes the work upon the best India gowns, or the painting upon their best skreens or purcellans, will find their beauty is all of this kind (that is) without order’.10

Temple’s ‘Chineses’, then, are not specifically Chinese: they are generically oriental, denizens of Cathay. Nor was he, in this instance, simply mistaken. The gardens of Japan were continually influenced by those of China,11 and Temple was aware of the similarity. A book that he is known to have read shows a naturalistic Chinese garden, with pine trees, a waterfall and jagged stonework; and he knew, too, that the Chinese imperial palace was surrounded by ‘large and delicious gardens’, containing ‘artificial rocks and hills’.12 Temple, then, was aware from his reading that Chinese gardens were irregular; while on those of Japan he had access to more privileged information. For he was accredited as ambassador to the one country in Europe to which Japan was still open by trade; that trade was conducted through Djakarta by the Dutch East India Company; and it was with this company that, in his trade negotiations with The Netherlands, he had had to deal.13

At the foot of the hills that crowd into Nagasaki harbour, a dusty tramline curves parallel to a muddy canal; between them runs a lane in a similar curve. These mark the outlines and the single street of Deshima: the artificial island, shaped like the paper of a fan, to which the Dutch were confined.14 Here was the only gateway between Japan and Europe; and the tall brush of an araucaria, carried by the Dutch from Indonesia, still stands in one of its gardens.

Of this ‘Dutch prison in Japan, for so I may deservedly call their habitation and factory at Nagasaki’, Englebert Kaempfer, the German naturalist who visited them there in the late seventeenth century, speaks in considerable detail and with considerable disdain. Once a year, however, restrictions were lifted; the island was left behind, and the Dutch travelled upcountry to pay homage to the shogun at Tokyo. On their return, they were allowed to halt at the more gracious imperial capital of Kyoto, still the major locus of the Japanese garden, and were taken to see its temples. On two of these occasions Kaempfer was with them. On the first, he observed ‘a row of small hills artfully made in imitation of nature’; and on the second, ‘a steep hill planted with trees and bushes in an irregular but agreeable manner’.15 ‘Irregular but agreeable’; ‘artfully made in imitation of nature’: …Temple’s sharawadgi.

Sharawadgi is a Japanese word connoting asymmetry; and no more characteristic concept could have arisen in that conversation reported to Temple. When the Chinese imperial city of Chang’an was reproduced in Japan as Kyoto, the chessboard perfection of its layout soon fell apart. The western half of the quadrilateral, after devastation by earthquake and fire, was allowed to revert to wilderness, while the eastern half flourished and overspread its original boundaries.16 The Chinese temple complex, likewise, had its symmetry overruled, in accordance with the asymmetrical groundplan of traditional Japanese architecture. This contrast has been pondered by K. Singer, who attributes it to geography: ‘Chinese civilisation seems one with China’s wide plains. Its foundations were laid in the North, where the…evenly balanced structure of the open spaces, obviously orientated to the cardinal points of the compass, had a visual force’. Here the alternating sequences of heat and cold, of light and dark, of Confucian fixity and Taoist flow, were integrated into symmetrical patterns. ‘The soil of Japan’, on the other hand, ‘essentially a world of thousands of great, small and minute islands, bays and valleys, is as much partitioned off and irregular as the immense Chinese plains are open and uniform. The cross of the four cardinal points is everywhere overlaid by a graceful wilderness of hills, volcanic ranges, fields and forests’. With asymmetry, in contrast with balance, goes motion as opposed to equilibrium, the passing in place of the permanent. ‘Chinese dwellings are cut into the soil, moulded from it, or joined to it in such a way that they appear to be part of the earth’s crust’. The archipelago of Japan, on the other hand, ‘is rocked by seismic shocks, invaded by storms, showered and pelted with rain, encircled by clouds and mists’; and its dwellings, accordingly, ‘attach themselves only lightly to the soil’.17 The contrast is immediately noticeable in their cities: where Suzhou is modelled in clay or carved in stone, Kyoto is the same structure translated into the idiom of timber. So too with their gardens. In China, the trailing willows and blossoming plums, the curving water channels and lotus-covered pools, subsist within a framework of solidity: the stone-paved courtyards opening out of one another, the lime-washed walls, the massive concatenations of rock. In Japan, however, where the sacred site was some numinous location in nature, the Taoist feeling for space and the spontaneous, for the understated and the inexpressible, given intense concentration by Zen, found a deeper echo.18 Here a garden may consist of pools of sunshine on a flooring of moss, or the shadows of maple in an earthen yard, or light glittering through a grove of bamboo. Or, where rocks are clustered in scattered islands, they acquire a curious permeability from their setting in gravel or sand: becoming, as in some romantic adagio, suggestions of form in a sea of silence.

Temple, then, could have spoken in The Netherlands to men who had stood in the gardens of Japan; and that this indeed was his source is confirmed by the very anomalies of his information. By the time that he wrote, sorowaji was obsolete in the standard language; but it survived in the south, where the Dutch settlement lay. The trick of speech through which it became shorowaji is still characteristic of the region; while the further change to sharawaji, or sharawadgi as Temple spelled it, is consistent with its having been filtered through Dutch.19 Deshima, too, unlocks the last of the word’s enigmas. Sorowaji is a verb – ‘would not be symmetrical’ – and not a noun,20 as Temple implied (‘they say the sharawadgi is fine’); and here again the solution is provided by Kaempfer. The authorities, he explains, had provided the island with a disproportionate number of interpreters

on purpose to make it needless for us to learn the language of the country, and by this means to keep us, as much as lies in their power, ignorant of its present state and condition… If there be any of our people, that hath made any considerable progress in the Japanese language, they are sure, under some pretext or other, to…expel him the country.

But if the Dutch were limited in their Japanese, their would-be interpreters were scarcely more fluent in Dutch:

the knowledge and skill of these people is, generally speaking, little else than a simple and indifferent connexion of broken words…which they put together according to the Idiom of their own tongue, without regard to the nature and genius of the language out of which they translate, and this they do in so odd a manner, that often other interpreters would be requisite to make them understood.21

We have arrived at the terminal point of sharawadgi. A Dutchman of little Japanese stands awestruck before a garden ‘irregular but agreeable’ and ‘artfully made in imitation of nature’. He enquires, and is answered in a ‘simple and indifferent connexion of broken words’. But out of this babel of mutual incomprehension the essential fact filters through: the sharawadgi is fine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am grateful to Peter Hayden, whose Biddulph Grange, Staffordshire: A Victorian Garden Rediscovered (London: George Philip, 1989), is a classic study of chinoiserie in the English garden, for his encouragement in this project.

NOTES

- 1. S. Lang and Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Sir William Temple and Sharawadgi’, The Architectural Review, 106 (December 1949), 391-2.

- 2. Oxford English Dictionary, s. v. ‘sharawaggi’.

- 3. Y. Z. Chang, ‘A note on sharawadgi’, Modern Language Notes, 45 (1930), 221-4; C. S. Ch’ien, ‘China in the Engish literature of the seventeenth century’, Quarterly Bulletin of Chinese Bibliography, English edn., n. s., 1 (1940), 351-84.

- 4. E. V. Gatenby, ‘The influence of Japanese on English’, Studies in English Literature, Tokyo, II (October 1931), 508-20; idem, ‘Sharawadgi’, Times Literary Supplement, no. 1672 (15 February 1934), 108.

- 5. P. Quennell, Alexander Pope: The Education of Genius, 1688-1728 (New York, 1968), 181n., quoted the Japan scholar I. Morris that while the word could not be Chinese, it might well be Japanese. M. Hadfield, A History of British Gardening, 3rd edn (London, 1979), 177n., while noting that ‘opinions differ’, thought it ‘probably not a Chinese word, but of Japanese origin’. R. Faber, The Brave Courtier: Sir William Temple (London, 1983), 142, noted that it ‘may apparently be Japanese, rather than Chinese’.

- 6. Sir William Temple, Works (London, 1757), III, 229-30.

- 7. Hadfield, History of British Gardening, 96-7.

- 8. William Bray (ed.), John Evelyn, Diary, 3 vols. (London, 1952), II, 173. Half a century later, the interior of a ‘Chinese House’ at Stowe would be described as ‘Indian Japan’: Michael Charlesworth (ed.), The English Garden: Literary Sources and Documents (Mountfield, 1993), II, 69.

- 9. D. Jacobson, Chinoiserie (London, 1993), 43; I. Tanaka, Japanese Ink Painting: Shubun to Sesshu, translated by B. Darling (New York and Tokyo, 1974), 93.

- 10. Temple, Works, III, 230. Hugh Honour, Chinoiserie (London, 1961), 69-70, attests to the growing popularity of Asian design at this time, from Nell Gwynne’s snuffbox to Queen Mary’s porcelain.

- 11. L. Kuck, The World of the Japanese Garden (New York and Tokyo, 1968), 19-22, 49, 115-23, 127, 149-56, 168-9, 226-7.

- 12. H. E. Woodbridge, Sir William Temple: The Man and Hs Work (New York and London, 1940), 282-4; A. Montanus, Atlas Chinensis, Englished by John Ogilby (London, 1671), 570-1; Temple, Works, III, 320-1. Montanus’ illustration is a Chinese woodblock print; his volume also shows planted lake shores with vistas of dramatic mountains and pavilions set at picturesque intervals (pp. 684-5); but his Atlas Japannensis (London, 1670) is by comparison a disappointment. Its illustrations have clearly originated in Europe, the shogun’s garden at Tokyo (‘Jedo’) being shown with matching avenues, parterres and a tree-lined circle (opposite p. 146). If Temple saw this – and it was ‘Englished’, like the Chinese volume, by the Ogilby who was a fellow-courtier of Charles II – it would have increased his reluctance to make sharawadgi a specific attribute of Japan.

- 13. G. B. Sansom, The Western World and Japan (New York, 1973), 177-8; C. R. Boxer, The Dutch Seaborne Empire, 1600-1800 (Harmondsworth, 1973), 220-1; Woodbridge, Sir William Temple, 100. In his essay ‘Upon the Cure of the Gout by Moxa’, Temple speaks of a Chinese medical practice under its Japanese name: R. A. Miller, The Japanese Language (Chicago and London, 1967), 259. His information came from a Dutch friend, who had had it from ‘several who had seen and tried it in the Indies’, and from an ‘ingenious little book’ by a ‘Dutch Minister at Batavia’ or Djakarta (Temple, Works, III, 238-65). Honour, Chinoiserie, 145; Hadfield, History of British Gardening, 117n.; and Quennell, Alexander Pope, 181n., suggest The Netherlands as Temple’s source; but no one, as far as I am aware, has attempted to trace the full course of the word’s odyssey past the obstacles described in the text.

- 14. Engelbert Kaempfer, The History of Japan, translated by J. G. Scheuchzer (Glasgow, 1906), II, 174; G. K. Goodman, Japan: The Dutch Experience (London and Dover, NH, 1986), 18-23.

- 15. Kaempfer, History of Japan, II, 174ff., 275-7; III, 118, 191. Kaempfer cannot have been Temple’s informant, as he made his journeys in 1691 and 1692, and the sharawadgi passage appears in the first and second editions of Temple’s Miscellanea: The Second Part, which were both published in London in 1690. In the first, where the essays are paged separately, it will be found on pp. 57-8 of that on gardens; in the second, on pp. 131-2 of the volume. As Kaempfer states, however, that the visit to the temples was a ‘custom of long standing…by degrees turn’d almost to a law’ (History of Japan, III, 117), it is evident that Temple’s source had access to the same experience.

- 16. I. Morris, The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan (Harmondsworth, 1969), 37-43.

- 17. K. Singer, Mirror, Sword and Jewel: The Geometry of Japanese Life (Tokyo, 1981), 107, 111-13, 144-7; H. Fingarette, Confucius: The Secular as Sacred (New York, 1972), 61-4; H. Welch, Taoism: The Parting of the Way (Boston, 1966), 21, 45, 158-9; F. Capra, The Tao of Physics (New York, 1984), 91-2. Singer finds a similar contrast between Chinese and Japanese verse-forms (pp. 133-5).

- 18. Kuck, World of the Japanese Garden, 67; Welch, Taoism, 159-61; Singer, Mirror, Sword and Jewel, 138-41, 147-8.

- 19. I owe these details to Professor M. Kanai, Tokyo University.

- 20. The modern equivalent is sorowanai desho, ‘would not harmonise, balance or match’: the Japanese subjunctive being a polite form of the indicative. Professor F. Daido, Tama Art University, has suggested that Temple’s informant conflated what he heard as sharawadgi with share and aji, both nouns which might be employed of a garden showing an impressive degree of taste (shareta niwa; aji ga aru niwa).

- 21. Kaempfer, History of Japan, II, 183-4, 203, 101.

The Secret Life of Sharawadgi

Built on Contradictions

It is ‘built on contradictions: it’s an art museum on an industrial structure. It’s a community space running a mile and a half through several neighbourhoods. It’s a botanical garden suspended over city streets’.

This is New York’s High Line, the former elevated railway which has been transformed into ‘an icon of contemporary landscape architecture’. It supplies a series of shifting vistas as it alternates between coppices, clearings and clusters of wildflowers. At the same time, ‘the High Line…never takes you away from New York… You can hear horns honking. You can see traffic and taxis’. ‘Unlike Central Park, it’s an immersion in the city, not an escape from it’.1

On the team chosen to reinvent the derelict line was the Dutch plantsman Piet Oudolf, his past work suggesting to the restorers an idealised version of the natural landscape they had come to love there: plants pushing up between the gravel ballast of the tracks, ‘almost… like nature trying to claw back the manmade structure and reclaim it… Piet composed grasses and perennials in naturalistic ways’.2

His achievements are at the heart of an exhibition in the Schunk Museum, Heerlen – ‘In Search of Sharawadgi: Landscape Works with Piet Oudolf and LOLA’ – of which the catalogue declares: ‘The planned eruptions of wild plants in the High Line Park wake us up from our feverish dream of symmetry… The…term sharawadgi has become synonymous with a style of landscape design or architecture that avoids rigid lines and symmetry to make the landscape appear organic and naturalistic’.3

Sharawadgi as Setting Free

The word ‘sharawadgi’ was reported by Sir William Temple, British ambassador to the Netherlands, who had had occasion to meet people who, serving on the island which was the Dutch enclave in Japan, had visited the gardens of Kyoto. Their naturalism, ‘without any order…that shall be…easily observed’, was particularly striking at a time in which European gardens were overwhelmingly symmetrical – ‘our walks and our trees ranged so as to answer one another’ – and mathematical – ‘at exact distances’.4

The principle became rooted in England after this account was paraphrased by Joseph Addison, a close friend of Temple’s secretary Jonathan Swift. And, since Addison was an ardent advocate of the parliamentary rule established under the Dutch king William III, the naturalistic layout was associated with a comparable decentralisation in politics, both being characterised as expressions of liberty, in contrast to the geometrical vistas of despotic France, monumentally expressed by Louis XIV at Versailles,5 as the exhibition catalogue notes.6

The genius of Addison, then, was that he transplanted the aesthetic of the Japanese garden, not through simplistic imitation, but in terms of his own, English, surroundings: ‘Why may not a whole Estate be thrown into a kind of Garden…? A Marsh overgrown with Willows, or a Mountain shaded with Oaks, are not only more beautiful, but more beneficial, than when they lie bare and unadorned. Fields of Corn make a pleasant Prospect, and if the Walks were a little taken care of that lie between them, if the natural Embroidery of the Meadows were helpt and improved by some small Additions of Art, and the several Rows of Hedges set off by Trees and Flowers, that the Soil was capable of receiving, a Man might make a pretty Landskip of his own Possessions’.7

Throughout the eighteenth century, in consequence, sharawadgi, as classically formulated by Capability Brown, expressed itself in a sea of grass, punctuated by clusters of trees and given focus by a body of water, which reached to the walls of the house:8 within which, by contrast, an elaborate symmetry reigned; the two united by the belief that, while the latter recreated the bodily surroundings of republican Rome, sharawadgi represented its libertarian spirit.9

Sharawadgi as Stability

The landowners, however, who sat in parliament, which asserted liberty vis-à-vis monarchy, in practice constituted an oligarchy, and felt threatened by the French revolution, which asserted liberty as egalitarian. Edmund Burke countered this with the statement: ‘The distinguishing part of our constitution…is a liberty connected with order’; and his friend Humphry Repton, the successor to Capability Brown, turned the eighteenth-century synthesis inside out. Formal gardens were now, typically, to surround the house, as if in a cordon sanitaire to keep the wildness of the surrounding parkland at bay; while for the house he favoured Gothic architecture: which had long been assimilated to sharawadgi, with a ‘bold irregularity of outline’ derived from accretions over the centuries, and an alleged origin in an avenue of trees. This now conferred a sense of age-old rootedness in the land that seemed to validate aristocracy.10

While, then, the first revolution in English landscaping established freedom in the garden and formality in the house, the second inverted this to freedom in the house and formality in the garden; and, as the nineteenth century advanced, the latter grew in elaboration, enriched by plant collectors, working world-wide and in the face of ‘hideous dangers and atrocious hardships’. ‘Victorian gardens’, notes Tim Richardson, ‘were stylistically as well as botanically acquisitive’, so that the ever-growing repertory of exotic species was supplied with exotic settings, redolent of such locations as China and Japan, or displayed in the form of the carpet bedding associated with public parks.11

Sharawadgi as Synthesis

Such ‘flat masses of strident colour’ were the particular target of William Robinson. Robinson has been described as Irish and irascible; and both of these he undoubtedly was. In American horticulture, he declared, he found ‘as much interest and novelty as a student of snakes could collect…in the land of St. Patrick’. But the full force of his vehemence was directed against that age-old antithesis of the English garden, Versailles: here he saw such soulless extravagance as to justify, in his view, the French revolution. As in England he deplored the lavish regimentation of flowers. In the words of Christopher Thacker, while he ‘appreciates, admires, understands’ the individual plants in such agglomerations; ‘he loathes – italics are weak to express Robinson’s detestation – the straitjackets in which they are confined’. And, in this prepossession, he ‘contributed to a revolution in garden design. His influence still flourishes in the current taste for informality, with bulbs massed among grass, mixed borders of native and exotic plants, and a softer and more subtle use of colour and plant associations’. He has indeed been described as ‘the conscience of modern horticulture’.12

In this capacity, he became embroiled with Reginald Blomfield: who, in creating ‘gardens with Tudor, Elizabethan, Jacobean and Caroline inflections’, ‘dogmatically opposed the freer and informal style of gardening…supported by…Robinson. He strongly advocated a return to formal gardening, using architectural shape, structure and materials, with plants as decorative adjuncts’.13

Into the resulting space stepped Gertrude Jekyll. Jekyll, it is suggested, was drawn to Robinson by his book The Wild Garden, ‘which must have come as a breath of fresh air…, extolling the beauties of English wild flowers to a society obsessed with…palms and bamboo groves and monkey-puzzle trees’. Accordingly, the two ‘became firm friends’, and Jekyll a regular contributor to Robinson’s journal The Garden. However, her principles were less exclusive: ‘she argued energetically in defence of colourful bedding plants, pointing out that it was not the plants’ fault that they were used in ignorant and foolish ways’. Jekyll, trained as a painter, had spent hours on end contemplating the sweeps of vivid colour in the landscape canvases of Turner; and she was to adopt similar values in her massing of flowers. So that when Blomfield asserted, as against Robinson’s vision of nature as the ‘perfection of harmonious beauty’, that ‘design was an intellectual abstraction relating to mass, void and proportion’ and the ‘job of the gardener…to prevent wayward plants from obscuring the plan so carefully worked out on the drawing-board’, Jekyll demonstrated that ‘this dichotomy of design and plantsmanship was…nonsense’.14 Which was the basis of her affinity with Edwin Lutyens.

Lutyens, owing to ill-health in childhood, lacked a regular education, instead roaming the lanes of his native Surrey, obsessed by its architecture: his own early essays in which, writes Richardson, are ‘steeped in the philosophy of the Arts and Crafts vernacular, with tiled roofs sweeping down in a low embrace of high gables, and leaded windows winking from half-timbered walls covered in climbing roses’. From these he went on to formulate ‘his own cool, modern version of the straightforward Surrey cottage style of his youth and then fitfully progressed towards a more romantic and formalised classicism’. As for Jekyll: ‘“Most of her gardens were based on a…plan, with terracing, pools and the shaping of lawns and borders contributing to the formality of the layout. Within this disciplined structure, Jekyll’s bold drifts of planting and ingenious use of colour would have appeared all the more rich and exuberant”’. As a consequence: ‘What was different about the work of Lutyens and Jekyll…was the way that the garden seemed to have been designed as all of a piece with the house’.15

Of his original encounter with Jekyll, Lutyens recalled: ‘We met at a tea-table, the silver kettle and the conversation reflecting rhododendrons’;16 and this image of plant and artefact fused might stand for the remarkable synthesis of nature and art that the two were to bring about. Their collaboration, wrote Lutyens’ biographer, ‘virtually settled that controversy, of which Sir Reginald Blomfield and William Robinson were for long the protagonists, between formal and naturalistic garden design. Miss Jekyll’s naturalistic planting wedded Lutyens’ geometry in a balanced union of both principles’.17

And at this point the English garden converged with the Japanese. ‘The Japanese garden’, declares Günter Nitschke, displays a ‘symbiosis of right angle and natural form… These two ways of perceiving beauty – as natural accident and as the perfection of man-made type – are not, to my mind, mutually exclusive. Quite the opposite: it is their simultaneous cultivation and conscious superimposition that best characterises the traditional Japanese perception of beauty… Each loses vibrancy if taken separately from the other. Without the contrast provided by a rectangular visual frame or rectilinear background, it would not be possible to recognise a handful of boulders, however carefully selected, as a garden’.18

Where, then, the first revolution in the English ensemble saw an irregular garden around a regular house, and the second a regular garden around an irregular house, the third saw regularity and irregularity conjoined in the garden itself; and this synthesis, lending itself to unlimited variety, is the basis of the masterworks which followed.

Sharawadgi as Secret

Hidcote was a house on a bare hill down which flowed a stream, later to be lined by a woodland walk. But the immediate requirement was shelter from the winds, which was secured by a complex of tall hedges. These enclose a short axis down the hill, with a long one crossing it; and, between these two, a series of outdoor rooms leading into one another. The result is described by Richardson: a ‘geometrically inventive plan of interlocking circles, squares and rectangles… The…wide, empty Long Walk at a right angle to the main allée, which suddenly frees up the heart of the garden, is well timed: a shaft of pure void that seems to shoot up from the surrounding landscape’; while the ‘pool garden, in which the great dark round almost completely fills the space, has always drawn admiration …for…its transcendent power’: ‘caught in a moment between space and time’.19 ‘Hidcote’, concludes Edward Hyams, ‘is a secret garden, a stillness’.20

Sissinghurst was ‘created with equal originality by the combined talents of Vita Sackville-West, the supreme artist-plantswoman, and her husband Harold Nicolson, who was able to help…give form to the planted areas and to link them together by strong axes into a satisfying design’. It was ‘the life-project of two intellectuals, expressive of their world-views, of their unconventional love for each other, and of a passion for the place itself’. Their garden ‘consists of a series of…outdoor “rooms”, asymmetrically arranged; formal in shape but informally planted’; says Richardson, ‘a succession of dreamlike episodes and intimacies’; or, as Nicolson himself phrased it, ‘a series of escapes from the world, giving the impression of cumulative escape’.21

Richardson, again, delicately conjures up the aura of the most celebrated of these ‘rooms’: ‘The White Garden is the essence of the dream that is Sissinghurst. It combines deep intensity of emotion with a feeling of ethereal suspension, because whiteness occupies space in a unique manner… It was made for the night, perhaps even more than for the day, because it is then…that the whites come into their own, almost fluorescent in the moonlight’.22

‘We have got’, declared Nicolson, ‘what we wanted to get – a perfect proportion between the classic and the romantic, between the element of expectation and the element of surprise’. The classic may be seen in the fact that most of the ‘narrow brick paths, encroached upon by plants and defined by yew walls, lead to some formal focus’; while the romantic is inherent in the site itself, encompassing as it does the remnants, dominated by their tower – a ‘unifying presence’ which ‘seems to make sense of all the different axial views and walks’ – of a half-ruined castle, also composed of ‘the red brick which mellows to such a beautiful soft rose colour’.23 Richardson explains: ‘At Sissinghurst the main house had fallen down or been removed, leaving a sequence of unconnected buildings and portions of walls’: making possible ‘the unique atmosphere created by a set of spaces that do not obey the rules…, where a fragmented layout and sometimes violently contrasting moods are the modus operandi’. ‘This’, he concludes, ‘is what makes it a greater garden, ultimately, even than Hidcote. We can never entirely know it. It bamboozles us with the illogicality of its effects and disorientations’.24

Assimilating the Satanic

Through all these shifting fashions in the garden, Temple’s original preference for sharawadgi over mathematics, echoed by Addison, seems to have sunk deeply into – or, it has been suggested,25 elicited something inherent in – the English psyche; and from time to time it burst forth in unexpected and original forms. Blake adapted it to the industrial revolution: in his contrast of dark satanic mills with an originally green and pleasant land, the machine was the new Versailles. Dickens pitted the living reality of a circus-girl’s horse against the abstraction of a dictionary definition which, in an educational system organised as for factory production, was the only acceptable method of apprehending its existence. Lawrence, once more, evoked the quivering, whinnying panic of a mine-owner’s mare as it was borne down upon by a shrieking and clattering train.26

Yet the High Line has assimilated even this industrialised landscape, so menacing to Blake, Dickens and Lawrence. As Sissinghurst transformed the Tudor ruin, converting the depredations of time into a cycle of decay and renewal, Oudolf has absorbed industrial civilisation itself into the processes of nature. ‘One of the most powerful impressions when we first stepped onto the High Line’, said one of its restorers, ‘was the effect of nature taking over the ruins’.27 This was in keeping with what the visionaries who salvaged the line had seen in it: ‘the spaces underneath…had a dark, gritty, industrial quality, and a lofty, church-like quality as well… There was a powerful sense of the passing of time. You could see what the High Line was built for, and feel that its moment had slipped away’:28 like some abbatial remnant in a landscape by Friedrich.29 And they were aware of their antecedents in Romanticism.30 The High Line has indeed been seen in terms of mono no aware, ‘the awareness of impermanence’,31 so closely anticipated by Vergil in lacrimæ rerum, as his hero moves from the destruction of Troy to its reconstitution in Rome.32

This vision is enacted, as at Hidcote or Sissinghurst, in a succession of contrasting spaces. Woodland is succeeded by grassland, thicket by meadow and wildflower, punctuated by open areas that borrow views of the streets with their fluctuating traffic or the flow of the Hudson river; and all along an irregular pathway.33

Wildest of Dreams

In planting the High Line, then, Piet Oudolf has encapsulated the entire history of sharawadgi. And, in the English layout named for him, he has returned to its origins. ‘Oudolf’, says the exhibition catalogue, ‘considers the design for the Hauser & Wirth art gallery in Somerset as the commission where he had the most freedom’. In the Oudolf Field, the ‘flowing beds smoothly blend into one another in a soothing rhythm of waves and curves, of textures and colours… The traditional view among gardeners is that spring should be a climax, full of growth and promise. Oudolf turned this idea around. He opted for a large share of perennials, including grasses, which are in bloom late in the season. He selected plants that look good in their final phase, and continue to express their character after they have died. At the start of winter, the colour spectrum gradually narrows to a subtle palette of brown hues’. But before that happens, the vista is of a strikingly beautiful, almost psychedelic brushwork of buff and gold, maroon and violet, scarlet and crimson and rose.34 Here Addison’s vision of ‘the natural Embroidery of the Meadows’, ‘helpt and improved by some small Additions of Art’, has found a realisation, one feels, beyond his wildest dreams.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is deeply grateful to the staff of the Schunk Museum, and particularly Joep Vossebeld, for warm support and encouragement in the writing of this essay.

NOTES

- 1. Oudolf, Piet and Rick Darke, Gardens of the High Line: Elevating the Nature of Modern Landscapes (Portland, OR: Timber Press, 2017), p. 13, 41, 104-5, 129, 216; Fabian de Kloe, Peter Veenstra, Joep Vossebeld & Brigitta van Weeren, Landscape Works with Piet Oudolf and LOLA: In Search of Sharawadgi (Rotterdam: naio10, 2021), p. 133; Joshua David & Robert Hammond, High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011), pp. 123, 125, 128.

- 2. The advocates of the High Line’s restoration were aware of the Promenade Plantée in Paris; and though this was ‘on a different kind of elevated rail structure…, made of masonry arches instead of steel’, it indicated that the New York scheme ‘was not a totally insane idea’ (David & Hammond, pp. 12, 14, 77). Another prototype, the Natur-Park Südgelände in Berlin, a former railyard which ‘repurposes trackways as pathways and is clothed almost entirely with the spontaneous vegetation that colonised the site after its abandonment’ (Oudolf & Darke, p. 34), was a far simpler matter; in New York: ‘We…had to remove everything first. We had to get down to the concrete slab that held the gravel ballast, to make repairs and put in a new drainage system… The site preparation work was the most expensive thing about the project… First the contractors painted yellow numbers on the steel railroad tracks, tagging them according to a site survey, so we could reinstall any rail in its original location’. Again: ‘We…brought a group of volunteers up to the…High Line…to harvest seeds from native plants so that we could replant them…after construction’ (David & Hammond, pp. 94-5, 100). Oudolf had previously worked on the Lurie Garden in Chicago, ‘slowly emerging from decades of decline for major American cities in the former industrial “rust belt”’, and laced with areas of ‘urban dereliction awaiting redevelopment. A particular eyesore was adjacent to the centre of downtown – as Mayor Richard M. Daley himself noted one day as he looked out of the window of his dentist’s office on Michigan Avenue. He began a campaign to clean up this messy patch of abandoned former railway land’; for which Oudolf designed what has been described as ‘a stylised representation of a natural prairie’, chiming with Chicago’s history: ‘The designer Wilhelm Miller had promoted prairie vegetation…at about the same time that Frank Lloyd Wright was leading the Prairie School of architecture’ (Piet Oudolf & Noel Kingsbury, Oudolf: Hummelo: A Journey through a Plantsman’s Life, New York: Monacelli, 2021, pp. 235-40).

- 3. de Kloe, Veenstra, Vossebeld & van Weeren, pp. 6, 16. This volume is a work of art in itself, beautifully designed and vividly illustrated, its text set in a typeface based on woodcut lettering: angular, individual and ‘akin to the spirit of sharawadgi’ (p. 187).

- 4. Sharawadgi has been traced to (i) sorowaji, ‘be irregular, unequal, asymmetrical’, (ii) possibly conflated with share and aji, ‘nouns which might be employed of a garden showing an impressive degree of taste’ (Ciaran Murray, Sharawadgi: The Romantic Return to Nature, Bethesda, MD: International Scholars, 1999, pp. 33-8, 273-5); and Temple stresses (i) the irregularity of the Sino-Japanese garden and (ii) the aesthetic subtlety involved in its arrangement. I have no difficulty with Wybe Kuitert’s assertion that share’aji is a term ‘still used by kimono fashion critics’, to do with the ‘symbolism of designed patterns in the dress…, and matching it to place, time and occasion’ (Wybe Kuitert: ‘How Japan inspired the English Landscape Garden: Sharawadgi!’, Shakkei, volume 21, number 3, Winter 2014/2015: 20-21): it could be taken as a corroboration and elaboration of point (ii).

- 5. Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 49-55, 62-4, 67-9, 72-3.

- 6. de Kloe, Veenstra, Vossebeld & van Weeren, pp. 16-17. The pattern was further overdetermined by the fact that the new astronomy, a preoccupation both of Temple and Addison, had discovered decentralisation in the universe (Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 137-63).

- 7. Murray, Sharawadgi, p. 73.

- 8. Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 233-4.

- 9. Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 169-70.

- 10. Murray, Sharawadgi, pp. 194-5, 256-7, 260-63. ‘The proclamation of egalitarianism had provided the French Revolution with one of its headiest appeals’ (John Keegan, A History of Warfare, London: Pimlico, 2004, p. 357).

- 11. Edward Hyams, The English Garden (New York: Abrams, n.d.), pp. 121-2, 126-8; Tim Richardson, English Gardens in the Twentieth Century: from the Archives of Country Life (London: Aurum, 2005), pp. 9-10; Geoffrey & Susan Jellicoe et al., ed., The Oxford Companion to Gardens (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), s. v. England: Nineteenth Century; Miles Hadfield, A History of British Gardening, 3rd edn. (London: Murray, 1979), pp. 322-8. At Biddulph Grange, a ‘bastion-like’ topiary construction, ‘to resemble the monumental entrance to a tomb’, and culminating in a topiary pyramid, is entered through a masonry portal along an avenue lined by sphinxes; while, through ‘a rocky tunnel, longer and darker than most garden tunnels, you arrive inside a Chinese pavilion, and look out from its crimson-painted balcony across a small, still lake, surrounded by bamboos, antique massy stones and exotic trees. Across the lake, a lacquered bridge, reflections, and beyond, high up as if in a mountain range, a weather-worn tower in the Great Wall’ (Hadfield, p. 354; Christopher Thacker, The History of Gardens, London: Croom Helm, 1979, pp. 240, 245; Jellicoe & Jellicoe, s. v. Biddulph Grange). The layout at Tully, though designed by a Japanese gardener, and including a tea-house and stone lanterns, was ‘devised as a symbol of man’s pilgrimage through life. From the Gate of Oblivion it passes through a cavern and winds along the Path of Childhood, up the Hill of Learning, across the Bridge of Matrimony, until it finally passes out through the Gateway of Eternity’ (Jellicoe & Jellicoe, s. v. Tully).

- 12. However one might qualify his responsibility for the revolution of which he is acknowledged to have been the instrument: ‘by raising a verbal tidal wave of opposition to bedding, and by coining the term “wild garden” to crystallise…other gardeners’ efforts, and by introducing these ideas to a very large number of readers who might not otherwise have discovered them, he was arguably more influential as a populariser than were the originators’ (Richard Bisgrove, William Robinson: The Wild Gardener, London: Frances Lincoln, 2008, pp. 62-3, 71, 85-7, 242-7; Thacker, p. 248; Richardson, English Gardens, p. 79). Piet Oudolf is repeatedly viewed in terms of Robinson (Richardson, English Gardens, pp. 201-2; Oudolf & Darke, pp. 22-4; Rory Dusoir, Planting the Oudolf Gardens at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Chicago, IL: Filbert Press, 2019, pp. 14-18; Oudolf & Kingsbury, p. 408).

- 13. Richardson, English Gardens, p. 93; Jellicoe & Jellicoe, s. v. Blomfield.

- 14. Richard Bisgrove, The Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll (London: Frances Lincoln, 1992), pp. 10-12; Jane Brown, Gardens of a Golden Afternoon: The Story of a Partnership: Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll (London: Penguin, 1994), p. 26.

- 15. Lutyens’ ‘romantic and formalised classicism’ may be seen at Viceroy’s House at Delhi: in form essentially Palladian, but with the body of the structure ‘assimilating…the Moslem polychrome tradition, expressed in the contrast of the red sandstone base with white above’, surmounted by a dome suggesting the Buddhist stupa (Brown, pp. 29-30; Richardson, English Gardens, pp. 46-7, citing Fenja Gunn, Lost Gardens of Gertrude Jekyll, London: Letts, 1991; Ciaran Murray, ‘The Raj as Romantic Vision’, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, V, ii, 2010, pp. 181-8). Arts and Crafts: Murray, Disorientalism: Asian Subversions, Irish Visions (Tokyo: Asiatic Society of Japan, 2009), pp. 87-108.

- 16. Brown, p. 19.

- 17. Bisgrove, Jekyll¸pp. 18, 137, citing Christopher Hussey, The Life of Sir Edwin Lutyens, 1950.

- 18. Günter Nitschke, Japanese Gardens: Right Angle and Natural Form (Köln: Taschen, 2007), pp. 10-12.

- 19. Richardson, English Gardens, pp. 111, 117-19.

- 20. Hyams, pp. 150-55.

- 21. Jellicoe & Jellicoe, s. v. Sissinghurst; Tim Richardson, Sissinghurst: The Dream Garden (London: Frances Lincoln, 2020), pp. 10, 31, 212.